Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

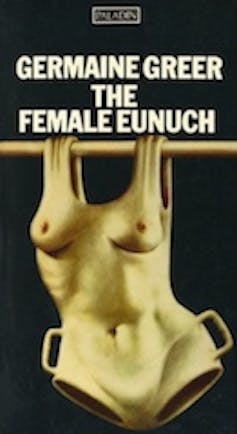

Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch changed lives. Published 50 years ago in October 1970, it exists in the popular imagination as a kind of shorthand for that world-historic moment when women said they’d had enough.

The book inspired women to challenge the ties binding them to gender inequality and domestic servitude. It broke marriages, or else caused some to be renegotiated on more equal terms.

The Female Eunuch told women the project of emancipation had stalled. Freedom would not be wrested from a process of reform, by “genteel, middle-class women” sitting on committees or signing petitions. To grasp their freedom, “ungenteel” women would need to “call for revolution”, “disrupt society” and “unseat God”.

Indeed, “marriage, the family, private property, and the state” were in the firing line.

Greer urged women to think beyond the stereotype patriarchal society had created for them, which limited their capacity to act. She likened the situation of the 1970s woman to that of a bird “made for captivity”.“The cage door had been opened but the canary had refused to fly out,” Greer wrote. “The conclusion was that the cage door ought never to have been opened because canaries are made for captivity; the suggestion of an alternative had only confused and saddened them.”

Women, she wrote, needed to “discover that they have a will”.

Read more: Friday essay: How Shakespeare helped shape Germaine Greer’s feminist masterpiece

Through the book’s five chapters — “Body”, “Soul”, “Love”, “Hate” and “Revolution” — Greer gradually built her famous motif of women as “eunuchs” or castrates, robbed of their natural energy. She wrote that in accepting this castrated or false identity, women had allowed the destruction of their instinct, inclination, will and capacity.

Greer’s book told women — in a hopeful way — that things could be otherwise. It told them to demand a better education, to pool their childcare arrangements, to share a better washing machine or other labour-saving appliance with women in the street. It told women to challenge men’s ownership of the means of production and consumer capitalism’s ownership of the soul.

Smashing sexual shibboleths

Greer famously drew attention to deeply entrenched cultural constructs that linked sex to shame and disgust, calling out the hypocrisy of a society that blamed women for men’s misogyny. “Women have very little idea of how much men hate them,” she wrote. “The man regards her as a receptacle into which he has emptied his sperm, a kind of human spittoon.”

These sexual shibboleths, she wrote, must be smashed. This was the point behind Greer’s widely discussed calls to go around bra-less and wear no underpants. Own your body, she urged women, its tastes and smells, including — most memorably — your menstrual blood.

“I must confess to a thrill of shock when one of the ladies to whom this book is dedicated told me that she had tasted her own menstrual blood on the penis of her lover,” Greer wrote. And yet, there are “no horrors presented in that blood, no poisons”.

Greer said women must question everything they had been taught about sex, love, romance, their bodies and their rights. Freedom was theirs, but they had to take it. Action was not just collective but individual too. Agency was everything. Grab any missile, break any rule. Do it now.

In this way, The Female Eunuch spoke to, and challenged, women directly. It asked, in its famous end line, “What will you do?”

Read more: Why it’s time to acknowledge Germaine Greer, journalist

Intellectual origins

Too few discussions of Greer’s work fully appreciate its intellectual origins in the libertarian ideas of the Sydney Push. Greer was born in Melbourne, educated by Irish nuns in a convent school, and yearned for a world beyond her own home, which was, she says, singularly bereft of books.

She moved to Sydney to study and fell in with a tearaway group of left libertarians known as the Push, a Bohemian movement with its origins in philosopher John Anderson’s Freethought Society.

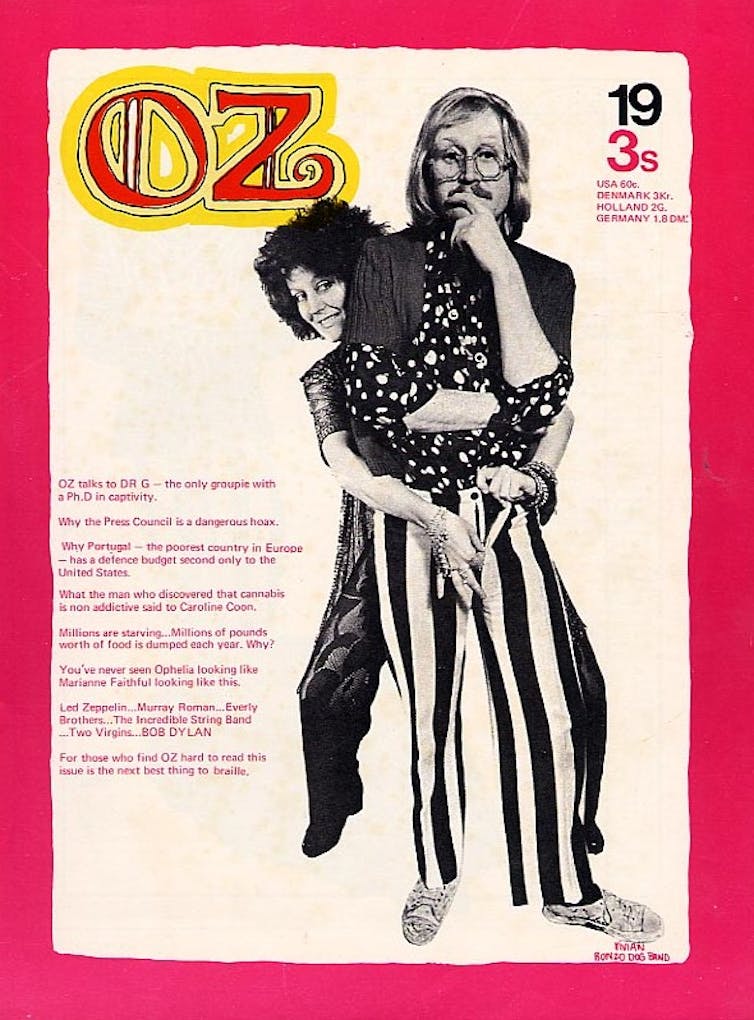

In Greer’s time, the Push included soon to be luminaries such as Clive James, Richard Neville — editor of Oz magazine and a doyen of the underground culture that gathered around it in London — and Lillian Roxon, “the abundant, the golden, the eloquent, the well and badly loved”, who became the New York-based correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald, author of the Rock Encyclopedia, and is one of five women to whom The Female Eunuch is dedicated.

The “Sydney line” espoused by the Push featured a heady mix of libertarianism and rule-smashing, anarcho-socialism. It preached “free love” and “opposition to authority”, encouraging members to live “freely” in an attitude of “permanent protest”.

Members of the Push pondered the “futility of revolutions” but nonetheless turned out for protests. The movement gave rise to seminal works of Australian feminism from Greer’s to Eva Cox’s and Wendy Bacon’s.

The formative influence of the Push led Greer to mount her social critique from the standpoint of “liberation feminism”, which she differentiated from so-called “equality feminism”. Equality was dismissed as a conservative aim, because it confers an illusion of power that merely re-entrenches the status quo.

Meaningful change — true “liberation” — required something more radical. Liberty could be terrifying. It was something not even men possessed. “The first significant discovery we shall make as we rocket along our female road to freedom is that men are not free,” wrote Greer, “and they will seek to make this an argument why nobody should be free”.

Media event

Intellectual discussions of The Female Eunuch often focus on the book’s appearance as a media event, and on Greer as a celebrity. It is a rich line of cultural inquiry, but occasionally leads critics to sell her work short, as flippant and ephemeral.

The book was commissioned by Sonny Mehta, who met Greer at a cafe in Soho on March 17 1969, when he was editor at MacGibbon and Kee. Mehta had an unerring eye for words, and an astonishing capacity to connect authors to an audience. He went on to become one of the most influential publishers of the late 20th century.

The Female Eunuch launched in London, but it was the extensive publicity campaign preceding the book’s entry into the American market that shaped its Anglophone reception. Its US publisher, McGraw Hill, outlayed a then extraordinary US$25,000 on promotion, including full-page advertisements in national newspapers.

During her 1971 book tour of the US, Greer appeared on television and radio. The New York Times called The Female Eunuch “the best feminist book so far”.

Always the controversialist, Greer gave interviews to magazines such as Esquire and Playboy. She trounced Normal Mailer in a New York debate, and often spoke back to journalists. “What kind of a question is that?” she would ask them.

Read more: The Town Hall Affair brings Germaine Greer’s 1970s feminist debate roaring into the present

In The Female Eunuch, Greer first signalled her often misinterpreted theories around rape and sexual consent. Greer has argued the idea of consent as it is written into law automatically positions women as subordinate and inferior. This sets up a situation that makes it almost impossible for a rape victim to get justice, as a perpetrator will only ever need to establish an element of doubt that consent was absent, by arguing that the victim had “given up” or “given in” or “hadn’t fought hard enough”.

The law, she argues, is a reflection of the wider misogyny diffuse in our culture, and is written in men’s interest. In more recent times, Greer has been accused of underplaying the seriousness of sexual assault and its impact on women.

Read more: Greer is right to say rape law has failings, but wrong to suggest its decriminalisation

In the 1970s, Greer openly discussed sexual violence and reproductive politics on prime-time TV, on talk shows like Dick Cavett’s, which Greer guest hosted for two nights. The results were explosive.

The Greer archives, housed at the University of Melbourne, contains thousands of letters that demonstrate the impact of Greer’s work and The Female Eunuch in particular. One female television viewer wrote about Greer’s talkshow appearance, “You could see minds and attitudes changing right on stage”.

She added, “Life magazine claims your appeal is that you ‘like men’. I claim that your appeal is that your intellect is welded to a very handsome ability to communicate”.

Of course, not everybody agreed. A reader of McCall’s magazine called a book extract from The Female Eunuch published in its pages “the most revolting ideas I’ve read in a woman’s magazine”.

Read more: Friday essay: reading Germaine Greer’s mail

Making the personal political

Greer became known — and still is — equally for her personality as for her ideas. This was perhaps inevitable because Greer had – and still has – a mesmerising capacity to make the personal political, and to play with the cultural gap between news and social norms.

Her work communicated her ideas on a mass scale and translated what were then the utterly unfamiliar ideals of feminism into everyday aspirations.

In the 1970s, The Female Eunch was dismissed with faint praise and even subject to panicked attacks from some feminists who saw the book as taking up too much space. In “The Selling of Germaine Greer”, published in The Nation, Claudia Dreifus argued that Greer was “shallow, anti-woman, regressive, three steps backwards” and “not the feminist leader she is advertised to be”.

In Australia, Beatrice Faust called Greer a “political bonehead”. Others appeared disconcerted by her dazzling polemics or dismayed — or simply uncomprehending — of the book’s left libertarian intellectual origins and its blunt insistence that before liberation can be achieved, women need to free themselves from the stereotypes that shackle them personally and sexually, as well as politically.

Today Greer’s work — and her legacy — remains divisive. Writers Mary Beard and Rachel Cusk have stood by the book, while others, including Naomi Wolf and Mary Spongberg, have been vocally critical of the author and her subsequent works. In 2010, Greer was vigorously attacked by playwright Louis Nowra in an infamous essay published in the The Monthly.

I first read The Female Eunuch at the age of 12, taking the age-spotted copy from my mother’s bookshelf. I read it again — this time from cover to cover — at 23. The Female Eunuch has never been out of print since it was published.

What still jumps out of the book’s pages is the strength and power of an author’s voice that speaks to its reader so directly.

The voice — like the author — is dazzling, erudite, anti-authoritarian, reliably contrarian, recklessly courageous, full of wit and great encouragement for unconventional ideas, tactics and behaviours, and utterly fearless in her search for social justice.

All this is why the marvellous “Germaine” exists for her reader on first name terms.

– ref. Friday essay: The Female Eunuch at 50, Germaine Greer’s fearless, feminist masterpiece – https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-the-female-eunuch-at-50-germaine-greers-fearless-feminist-masterpiece-147437