Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Bain Munro Attwood, Professor of History, Monash University

The Conversation is running a series of explainers on key figures in Australian political history, looking at the way they changed the nature of debate, its impact then, and it relevance to politics today. You can read the rest of our pieces here. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

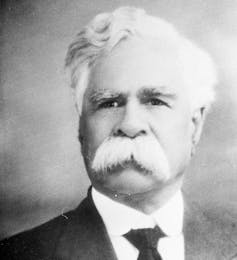

William Cooper is not a household name, but he should be. This Yorta Yorta elder is one of Australia’s most formative political leaders.

In the 1930s, he began a remarkable political campaign, pushing for Indigenous rights and recognition, nearly all of which have significant implications for Australian politics today.

Early life

Cooper was born on the junction of the Murray and Goulburn rivers in December 1860. He was profoundly influenced by his people, who had demanded and won a reservation of land in the 1880s, which they called Cumeroogunga.

Yorta Yorta people farmed Cumeroogunga into the 1900s, only to lose it and have their families and community broken up by repressive policies of the New South Wales Board for the Protection of Aborigines in the 1910s and 1920s.Cooper escaped the most severe of state protection boards’ special laws at the time, which denied Aboriginal people basic rights such as freedom of movement, custody of their children and control over personal property.

But he knew the suffering the laws caused and still had a very hard life, denied the opportunities enjoyed by most non-Indigenous Australians. Apart from anything else, this meant he suffered enormous poverty.

Christian influence

Importantly, in his early life, Cooper also acquired the means to understand and fight against his people’s oppression. In his teens, he was taken under the wing of evangelical Christian missionaries, Daniel and Janet Matthews, at the Maloga mission on the banks of the Murray River.

Their teachings were fundamental to the political work Cooper would eventually undertake. They had a view of humanity that encompassed all people as God’s children, and so held the lives of Aboriginal people mattered, too. This provided a powerful antidote to the prevailing racial prejudice Cooper experienced and witnessed.

The Matthews saw God and religious principles as a higher order than government. And they provided a prophetic or predictive view of history that promised salvation for the Yorta Yorta, just as the Bible, especially the Book of Exodus, had promised to the persecuted and suffering Israelites.

Read more: Charles Perkins forced Australia to confront its racist past. His fight for justice continues today

It is understood Cooper spent much of 20s on and off missions and then earned a living working as a shearer, drover, horse-breaker and general rural labourer.

He was a member of the Shearers’ Union and Australian Workers’ Union. He also acted as a spokesman for Aboriginal workers in western New South Wales and central Victoria, having a “longing to help his people”. After returning to Cumeroogunga in his 60s, he moved to Melbourne, so he could get the age pension.

Petitioning the King

Now in his 70s, Cooper began a remarkable political campaign. This had several strands, many of which continue to have significance in Australian politics today.

First and foremost, in 1933 Cooper drew up a petition to King George V. With more than 1,800 signatures by the time it was presented to the federal government in 1937, the petition’s central demand was representation for Aboriginal people in the Commonwealth Parliament. This call for a federal MP who would be chosen by Aboriginal people was, if you like, a demand for a Voice to Parliament.

Cooper believed this was crucial, as government laws about Aboriginal people were made without any consideration of their opinions. He argued Indigenous perspectives differed markedly from those of white Australians – which Cooper called “thinking black”.

Cooper was heir to a tradition among Aboriginal people in New South Wales and Victoria that held they had a special relationship to the British king or queen. Certainly, Cooper believed Aboriginal people had a right to appeal to the British Crown on the grounds that it still had a responsibility for them because of duties it had undertaken to perform in the past.

Regrettably, prime minister Joseph Lyons did not pass the petition on to Buckingham Palace, and it has never been found in any archive. But in 2014, a copy finally reached Queen Elizabeth, after his grandson Boydie Turner travelled to London.

Equal rights and ‘uplift’

In 1936, Cooper founded the Australian Aborigines’ League, which he envisaged as an organisation to represent all Aboriginal people.

Under his leadership, the league developed a program to call for the rights and privileges that other Australian citizens enjoyed, while also seeking the “uplift” of Indigenous people, so they could overcome the disadvantages they suffered.

“Uplift” entailed a claim for special rights for Aboriginal people — to land, capital and other resources — that rested on their disadvantage, rather than their status as the country’s Indigenous or First peoples.

But in the course of demanding the rights of citizenship and “uplift”, Cooper repeatedly sought to draw attention to his ancestors’ prior ownership of the land and their subsequent dispossession, displacement and decimation.

He did so in order to remind white Australians of their obligations to Aboriginal people, incurred as a result of this history. As Cooper noted in 1938,

Surely the Commonwealth, which controls all that originally belonged to us, could make what would be a comparatively meagre allowance for us, by way of recompense.

To remind people of Australia’s black history, Cooper called for a “Day of Mourning” to mark Australia’s sesquicentenary in January 1938 and an “Aborigines’ Day” to be held in the nation’s churches every year on the Sunday closest to Australia Day.

Protest against Nazi persecution

Cooper and the League also rejected government policies advocating for the absorption of Aboriginal people into Australian society. Instead, he asserted a vision of Aboriginal people as a permanent and ongoing community in Australia. As he said in 1936,

all thought of breeding the half-caste white, and the desire that that be accomplished, is a creature of the white mind. The coloured person has no feeling of repugnance toward the full blood, and in fact, he feels more in common with the full blood than with the white.

Cooper and other members of the league identified very strongly as a persecuted racial minority and made common cause with others beyond Australia’s shores, including the Jewish people.

In the incident for which Cooper now seems to be best known by non-Indigenous Australians, in December 1938 he led a protest against Nazi persecution to the German Consulate in Melbourne.

Inspiring a new generation

Cooper’s life and work seem astoundingly relevant for today. But during his life his campaign for rights for Aborigines fell on deaf eyes as far as government was concerned.

As he lamented in 1937,

We asked [for] bread. We scarcely seem likely to get a stone.

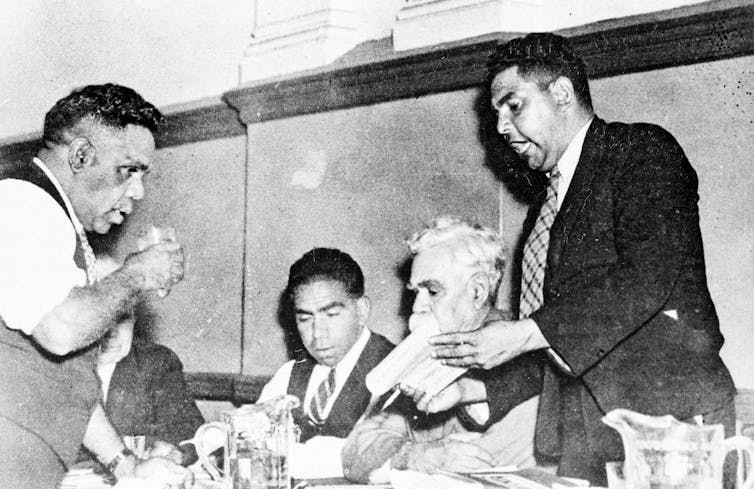

Yet, by the time he passed away in March 1941, he had inspired a new generation of Aboriginal leaders, most notably his grand-nephew Doug Nicholls but also the Onus brothers, who became prominent in the struggle for Aboriginal rights in the immediate post-war period.

His notion of “thinking black” would in time also catch the imagination of yet another generation of Aboriginal leaders, such as Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

Most importantly, perhaps, Cooper is remembered above all else for his prescient call for an Aboriginal voice to Parliament.

Through this, and his fight to overcome Aboriginal disadvantage, he continues to speak to us today.

– ref. William Cooper: the Indigenous leader who petitioned the king, demanding a Voice to Parliament in the 1930s – https://theconversation.com/william-cooper-the-indigenous-leader-who-petitioned-the-king-demanding-a-voice-to-parliament-in-the-1930s-140056