Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Paul Gray, Associate professor, Jumbunna Insitute for Indigenous Education and Research, University of Technology Sydney

The Conversation is running a series of explainers on key figures in Australian political history, looking at the way they changed the nature of debate, its impact then, and it relevance to politics today. You can also read the rest of our pieces here.

In his pursuit of justice and self-determination for Aboriginal people, Charles Perkins, an Arrernte and Kalkadoon man and lifelong civil rights activist, held a mirror up to Australia.

Through his outspoken and sometimes controversial advocacy, he challenged Australia to confront its own history. He kept a spotlight on discrimination and inequality, making many people uncomfortable, and in doing so, opened the space for debate and opportunities for change.

As Aboriginal rights campaigner Tom Calma said of Perkins:

If we look back at each of the major developments in Indigenous policy since the 1960s – Charlie was always there.

From football to activism

Perkins was born in 1936 in Alice Springs and spent his early life on an Aboriginal reserve under the tight control of authorities, forced to live with curfews and the threat of interventions by police and welfare officials. Nevertheless, Perkins also remembered the small joys of spending time with his family and people.

At about 9-years-old, Perkins was taken to a hostel in Adelaide. This provided the chance for an education not offered to Aboriginal children in Alice Springs, but the institutional setting was strict and lacked the love and sense of belonging of home.

Perkins described this period as one of the great tragedies of his life, lamenting his lost youth and disconnection from family, kin and culture.

At 16, after confrontations with hostel administrators, Perkins was forced to leave. Adelaide’s football community offered refuge. Naturally athletic and determined to win, he thrived and was soon offered a trial with professional clubs in the UK.

During a game at Oxford University, a seed was planted:

I thought about Aboriginal affairs and what my contribution might be. I thought, ‘I must go to university. I’ve got to prepare myself educationally’.

And in 1959, he turned down an offer to join Manchester United, instead returning to Australia to enrol at the University of Sydney.

Read more: As the federal government debates an Indigenous Voice, state and territories are pressing ahead

Starting the fight for self-determination

It was during this time that Perkins became an active participant in the Aboriginal rights movement, organising petitions and speaking publicly about the discrimination he and his peers experienced.

In between studies and football, Perkins worked with the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs, helping Aboriginal people in Sydney secure housing and employment and providing a place to socialise and organise politically.

Like other Aboriginal leaders of this time, Perkins’s vision prioritised basic rights – adequate housing, education and employment opportunities – as the building blocks of self-reliant communities, able to confidently engage with non-Indigenous society on their own terms.

He was mindful of the debilitating psychological impact of protection-era policies and saw strength and resilience in Aboriginal culture and values. He told an audience in 1974:

What I would think the Aboriginal people want […] is dignity, self-respect and a place in Australian society under some of the terms we dictate.

This included land rights, an end to discrimination and an Aboriginal commission to ultimately replace the functions of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

The impact of the Freedom Ride

Perkins also drew inspiration from the US civil rights movement, particularly Martin Luther King Jr’s belief in non-violent protest and the 1961 Freeedom Rides across the South.

In what became a significant event of the Indigenous rights movement in Australia, Perkins led the Student Action for Aborigines on its own Freedom Ride — a bus tour of country NSW in 1965.

Stops in Walgett, where Aboriginal people could not enter the RSL, and Moree, which excluded Aboriginal children from swimming in the local pool, attracted violent opposition and national attention, forcing Australia to grapple with these issues.

This set the scene for the 1967 referendum, in which Australians overwhelmingly voted to amend the constitution to allow parliament to make laws for Aboriginal people, shifting the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians.

With the Commonwealth taking a role in Aboriginal affairs, Perkins saw the potential for national change, working within the administrative system to influence policies that affected Aboriginal people.

‘A burning passion for advancing the interests of his people’

In 1969, Perkins joined the Office of Aboriginal Affairs. But change was slow, as the new department grappled with entrenched bureaucracies still focused on the assimilation of Aboriginal people.

Perkins persevered, though, and worked to establish institutional mechanisms to empower Aboriginal people to take charge of their own affairs. He led the National Tribal Council, with a vision of Aboriginal people

controlling their own destiny, electing their own representatives and speaking out in a strong and democratic manner whenever the need may arise.

His outspoken approach created significant tension. Prime Minister Bob Hawke noted Perkins

sometimes found it difficult to observe the constraints usually imposed on permanent heads of departments because he had a burning passion for advancing the interests of his people.

When Perkins was later appointed as the first Aboriginal person to lead the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, he brought a unique, hands-on approach to the role. He consulted widely with Aboriginal communities, spending significant time on the road.

However, following setbacks in Native Title legislation and friction with his minister, Perkins resigned in 1988. He was subjected to intense scrutiny and false allegations, but was exonerated following multiple inquiries. Hawke later acknowledged these travails as “grossly unfair”.

Read more: Lessons of 1967 referendum still apply to debates on constitutional recognition

A new generation carrying on his work

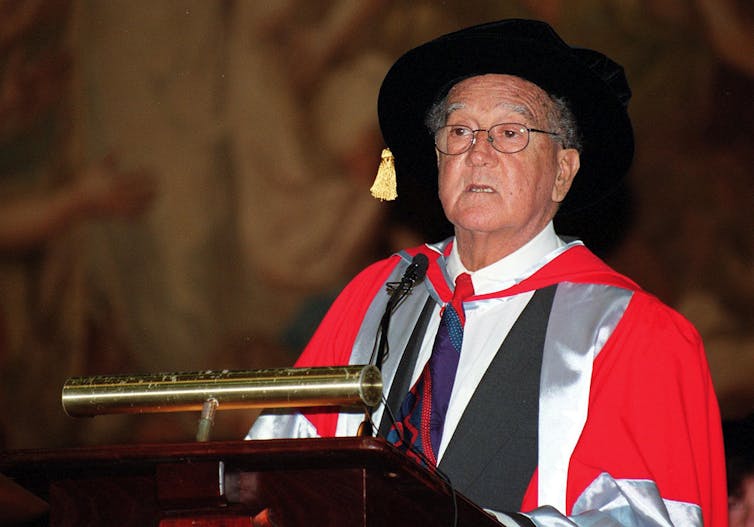

Perkins believed in the transformative power of education, becoming one of the first Aboriginal university graduates. This legacy continues to be felt today, with almost 20,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students enrolled at universities around the country.

A scholarship has also been established in his name to send Aboriginal students to study at the world’s best universities.

Perkins passionately believed Aboriginal people had a unique contribution to make to our society – they represented Australia’s conscience and could give the country its soul.

He and his contemporaries continue to inspire generations of Aboriginal people to take their rightful place in the future of this country, appreciating the solutions lie in Aboriginal communities themselves.

This legacy is present in the continued calls for recognition of Aboriginal peoples’ dignity and self-determination. It’s also felt in the push for a new relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people that recognises the special place of Aboriginal people on our Country – the unfinished business of our nation.

Reflecting on his own contributions to Australian society, Perkins once said,

I’m here today, gone tomorrow, and I’ve only just played a small role like other Aboriginal leaders do, but we’re only passing, you know, ships in the night really. And where the answer lies, is with the mass of Aboriginal people, not with the individuals.

Read more: Three years on from Uluru, we must lift the blindfolds of liberalism to make progress

– ref. Charles Perkins forced Australia to confront its racist past. His fight for justice continues today – https://theconversation.com/charles-perkins-forced-australia-to-confront-its-racist-past-his-fight-for-justice-continues-today-139303