Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Peter McPhee, Emeritus professor, University of Melbourne

In this time of pandemic, our authors nominate a work they turn to for solace or perspective.

I’m one of those fortunate people for whom the direct experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has thus far been felt only through isolation from close friends and family and away from the pleasant routines of campus. Indirectly, however, it has been felt as a deep ultimatum from the earth about the interactions of its inhabitants.

Books are both solace and provocation at such a time. Reading Rachel Cusk’s latest collection, Coventry, prompted me to read her entire oeuvre in sequence, as I also did as I reread Richard Ford, and as I will now pursue with Patrick Modiano.

Why this urge to read a writer’s corpus in strict order? Was this my subconscious desire to restore order to a disordered world? Or just the depressing signs of a tidy mind? A linear imagination? Whatever the case, it has been satisfying.

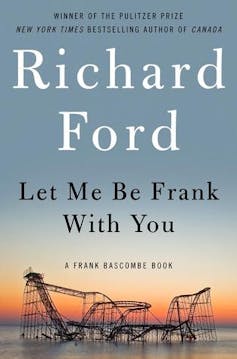

Ford’s prize-winning trilogy of Frank Bascombe novels – The Sportswriter (1986), Independence Day (1995) and The Lay of the Land (2006) – are a landmark in recent American literature, but it is his follow-up Let Me Be Frank With You (2014) that I have most relished returning to. The four interwoven “long stories” (Ford’s term) are his poignant, often hilarious, reckoning with environmental catastrophe and mortality.

Frank is now 68 and retired eight years from the real estate business he had run along the New Jersey Shore. He has moved inland to comfortable, white, “asininely Tea Party” Haddam with second wife Sally Caldwell. He travels to Newark weekly to greet “weary, puzzled” troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, and reads to the blind on his local radio station. His current choice for them is V.S. Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival: “they’re pissed off about the same things he’s pissed off about”.

Frank is dealing with his ageing body: he is recovering from prostate cancer and Sally keeps telling him to lift up his feet when he walks to avoid “the gramps shuffle”. Frank now listens to Aaron Copland and is trying to read The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying.

Frank deals routinely, if mostly affectionately, in ethnic and racist labels. He still calls black Americans “Negroes” but plainly prefers them to others of his compatriots: “It’s no wonder they hate us, I’d hate us, too”. Frank is a Democrat; he’s gratified that Obama likes Copland’s Fanfare.

The four interwoven stories unfold across the fortnight before Christmas 2012 in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which had hit the Jersey Shore on 29 October, shattering coastal buildings and killing scores of locals.

The presidential election has just been held: an Obama-Biden sign has been repurposed to read “WE’RE BACK. SO FUCK YOU, SANDY”. Other signs along the Shore warn “LOOTERS BEWARE!”. One, notes Frank, “merely says NOTHING BESIDES REMAINS (for victims with a liberal arts degree)”. His own former house on the shore has disintegrated.

Frank is awe-struck: “There’s something to be said for a good no-nonsense hurricane, to bully life back into perspective” but admits his fear that “something bad is closing in – like the advance of a shadow across a square of playground grass where I happen to be standing”.

The people of the Jersey Shore have various explanations for the hurricane: his ex-wife believes it was a “bedrock agent”, others think it was somehow Obama’s doing to prevent people voting for Mitt Romney. No-one refers to climate change.

Richard Ford interprets and survives a world undone by calamity and death through the encounters Frank has with four individuals: a former client to whom Frank had sold his own house eight years earlier; a reserved, sad and gracious black woman who visits Frank’s new house where 40 years earlier her father had killed her mother, brother and himself; his ex-wife Ann, who has Parkinson’s and has moved to an aged-care facility “determined to rebrand ageing as a to-be-looked forward-to phenomenon”; and an old friend Eddie.

This novel is Ford at his finest. Sharp satire is captured in barbed turns of phrase. Unforgettable, somehow rootless, characters stud the stories. Ford combines the meticulous attention to domestic detail of contemporaries Philip Roth and John Updike with the “dirty realism” of Raymond Carver. His precise, gritty tone is perfect – and strangely consoling.

Ford’s ultimate consolation offered to us is expressed through a brief final encounter, an epiphany of decency through environmental calamity and personal despair. After all, “love isn’t a thing”, he notes, “but an endless series of single acts”.

– ref. Art for trying times: reading Richard Ford on a world undone by calamity – https://theconversation.com/art-for-trying-times-reading-richard-ford-on-a-world-undone-by-calamity-142816