Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Nathan Kettlewell, Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Economics Discipline Group, University of Technology Sydney

We live in a culture that values “experiences”. These are often promoted in the media, and by those selling them, as vital to enhancing our well-being.

We all know big life events like marriage, parenthood, job loss and the death of loved one can affect our well-being. But by how much and for how long?

We set out to measure the effect of major life events – 18 in total – on well-being. To do so we used a sample of about 14,000 Australian adults tracked over 16 years. Some of our results were expected. Others were surprising.

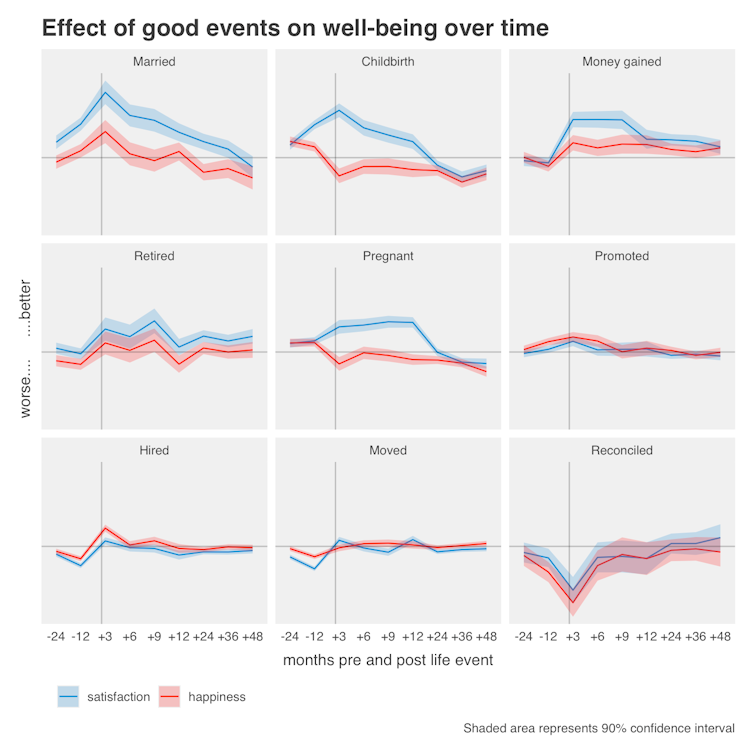

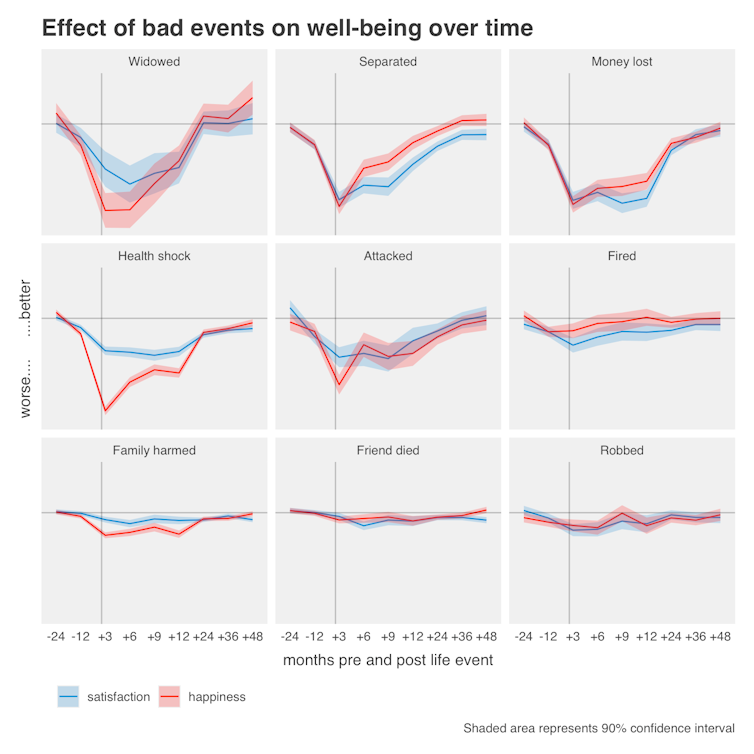

Overall, our results show good events like marriage improved some aspects of well-being, but bad events like health shocks had larger negative effects. For good and bad events, changes in well-being were temporary, usually disappearing by 3-4 years.

Here are some of our most interesting findings.Happiness versus life satisfaction

Our study distinguished two different aspects of well-being: “happiness” and “life satisfaction”. Researchers often treat these as the same thing, but they are different.

Happiness is the positive aspect of our emotions. People’s self-reported happiness tends to be fairly stable in adulthood. It follows what psychologists call “set point theory” – people have a “normal” level of happiness to which they usually return over the long run.

Read more: Happiness hinges on personality, so initiatives to improve well-being need to be tailor-made

Life satisfaction is driven more by one’s sense of accomplishment in life. A person can be satisfied, for example, because they have a good job and healthy family but still be unhappy.

Life events often affect happiness and life satisfaction in the same direction: things that make you happier tend to also improve your life satisfaction. But not always, and the size of the effects frequently differ.

In the case of having a child, the contrast is stark. Right after the birth, parents are more satisfied but less happy, possibly reflecting the demands of caring for a newborn (eg. sleep deprivation).

Changes are temporary

After almost all events (both good and bad), well-being tends to return to a personal set point. This process is known as the hedonic treadmill – as people adapt to their new circumstances, well-being returns to baseline. This has been found in other studies as well.

The good news is that even after very bad events, most people seem to eventually return to their set-point well-being level. Even after an extremely bad event such as the death of a spouse, people’s well-being generally recovers in two to three years. This doesn’t mean they don’t carry pain from the experience, but it does mean they can feel happy again.

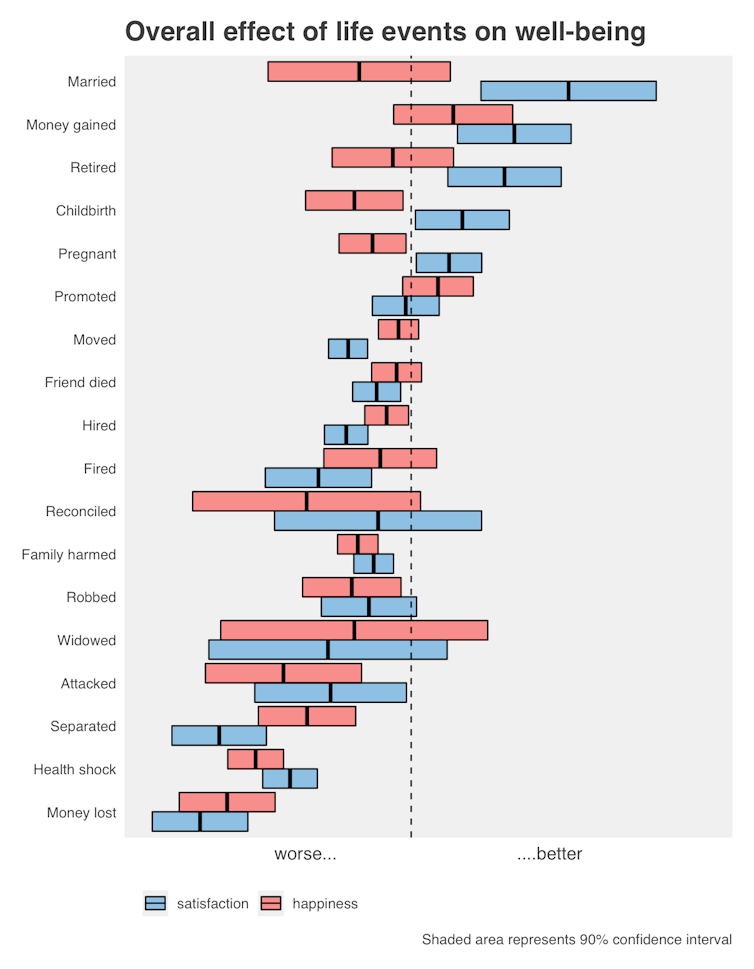

Bad events affect us more

The detrimental effects of bad events on well-being outweigh the positive effect of good events. Negative effects also last longer. This is partly because most people are happy and satisfied in general, so there is more “room” to feel worse than better. In fact, we can’t confidently say there is any positive cumulative effect of good events on happiness at all. However, marriage, retirement, childbirth and financial gains all temporarily improve overall life satisfaction.

Our finding that “losses” hurt more than “gains” mirrors decades of behavioural economics research showing people are generally “loss averse” – going to more effort to avoid losses than to chase gains.

Read more: Explainer: what is loss aversion and is it real?

The bad events that have the largest total effects are death of a spouse or child, financial loss, injury, illness and separation.

Small, fleeting effects

Starting a new job, getting promoted, being fired and moving house are events that people often fixate on as either stressful or to be celebrated. But, on average, these don’t seem to affect well-being that much. Their effects are comparatively very small and generally fleeting.

This could be because of differences in the nature of these events for different people, or that they frequently occur. For example, being fired can be devastating. But for someone close to retirement who receives a large redundancy payment and moves to the coast, it might be a positive experience.

An important caveat to our study is that it reflects the average experiences of people. There are likely to be some people who experience long-lasting improvements in well-being after good events. There will also be people who experience sustained decreased well-being after bad events. In future work we hope to identify these different people and isolate the characteristics that predict what responses to different events will look like.

The things that matter

Our results caution against chasing happiness through positive experiences alone. The impact, if any, seems small and fleeting, as the hedonic treadmill drags us back to our own well-being set point.

Read more: The paradox of happiness: the more you chase it the more elusive it becomes

Instead, we might do better by focusing on the things that protect us against feeling devastated by bad events. The most important factors are strong relationships, good health and managing exposure to financial losses.

In 2020 we might also take consolation from the fact that, although it will take time, our well-being can recover from even the worst circumstances.

We humans are a resilient bunch.

– ref. Marriage and money help but don’t lead to long-lasting happiness – https://theconversation.com/marriage-and-money-help-but-dont-lead-to-long-lasting-happiness-140431