Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute

After managing the first stage of the COVID-19 crisis so effectively, the government now faces a bigger challenge: getting us back to work.

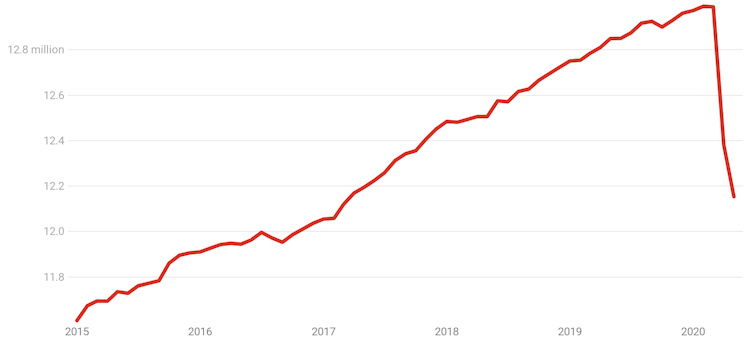

The official employment figures indicate the scale of what’s needed. In the past two months number of Australians with a job has fallen by 835,000. Millions more are in jobs kept on life support by JobKeeper.

Employed Australians, total

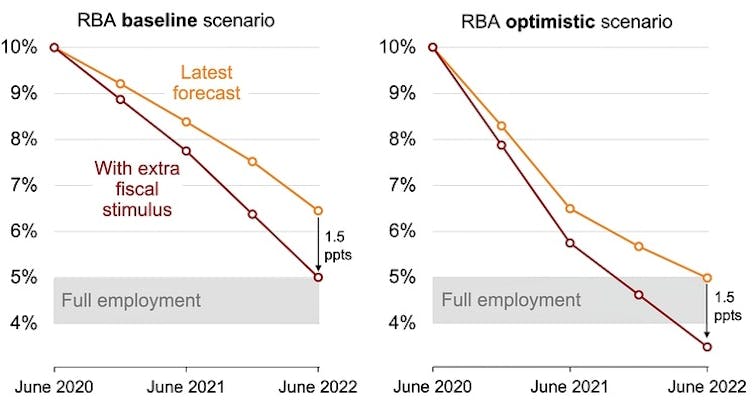

The Reserve Bank’s latest public forecast has the unemployment rate peaking at 10% and then falling to 6.5% (baseline scenario) or 5% (optimistic scenario) by mid-2022.

In Grattan Institute’s latest report, The Recovery Book, released this morning, we argue this isn’t ambitious enough.The case for ambition

The bank and the government ought to aim for something better, closer to 4.5%.

This is the rate it has previously identified as “full employment”, the lowest Australia can sustainably achieve without stoking inflation.

It would mean bringing unemployment down 1.5 percentage points further than it might otherwise fall over the next two years – to somewhere between 4% and 5%.

Projected unemployment with and without extra fiscal stimulus

The bank has passed the baton

With the bank’s cash rate already cut to 0.25%, conventional monetary policy (cutting the cash rate) has run out of steam.

Unconventional policy will help.

The Reserve Bank is advancing cheap money to private banks for onlending to businesses, buying government bonds to keep the three year bond rate near 0.25%, and has pledged to keep the cash rate at 0.25% for the next three years.

The bank can and should do more, but the rest will have to be done by government spending and tax measures, so-called fiscal policy, of the kind that has already been proved effective in suppressing unemployment.

We’ll need $70 to $90 billion

We estimate that reducing unemployment by 1.5 percentage points by mid-2022 would require additional stimulus of A$70 billion to A$90 billion over the next two years, equivalent to between 3% and 4% of GDP.

This is on top of the more than $160 billion committed to JobKeeper and other coronavirus supports to date.

Here’s how we make the calculation.

First, to reduce unemployment by that much we estimate that real gross domestic product needs to grow by about 4 percentage points more than forecast over the next two years.

The estimate is based on previous work by economist Jeff Borland. Jeff kindly updated his calculation with us for this article, finding that each one percentage point increase in annual GDP growth reduces the unemployment rate by around 0.38 percentage points.

Read more: Why even the best case for jobs isn’t good. We’ll need more JobKeeper

Second, we assume each dollar of stimulus in a particular year increases GDP in that year by between 80 cents and one dollar (some of the rest is saved and some leaks overseas).

This estimate of “fiscal multiplier” is slightly higher than that used by treasury during the global financial crisis but is in line with recent academic work finding that stimulus measures are more effective when monetary policy is out of ammunition.

If the fiscal multiplier isn’t as high – or if the recovery is more sluggish than expected, more stimulus might be needed.

There’s little risk of overkill…

A few weeks ago Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe raised the possibility that the crisis had pushed the minimum sustainable rate of unemployment higher, from 4.5% to nearer 5%, on the face of it making a case for less ambition.

His concern was “scarring” – the risk that some of the people who lose their jobs will become so damaged they become unsuitable for future employment, meaning that employers looking for staff would rather bid up the wages of existing workers than employ them, fuelling inflation.

But, if anything, his concern is a powerful argument for spending more, and more quickly, in order to avoid scarring. There’s good evidence sustained high unemployment hurts the economy in the long term.

Read more: The charts that show coronavirus pushing up to a quarter of the workforce out of work

And if the extra spending did fuel inflation, it mightn’t be such a bad thing.

Inflation has been below the bank’s target for years. If it gets above it and becomes a problem, the bank can dampen it by raising rates.

…and little time to lose

The extra stimulus will need to be announced soon: on or well before the federal budget scheduled for October. Fiscal measures take time to have their biggest effect.

We are facing a “fiscal cliff” when measures including JobKeeper and the enhanced JobSeeker payment are withdrawn at the end of September. To escape it, they will need to be wound down more gradually, as the international Monetary Fund warned last week.

There are plenty of ways to maintain support including further cash payments to households, along the lines of those in the global financial crisis showed were effective in boosting spending, as well as spending on things such as social housing, roads and school maintenance.

Fear of debt needn’t hold us back

Extra stimulus will mean extra government debt. But the Australian government can now borrow for 10 years at a fixed interest rate below 1%. Adjusted for inflation, that’s a negative real interest rate, making debt more affordable than it has been in living memory.

There will naturally be concerns that further debt will place a burden on younger generations. But they are the generations that will be lumbered with the costs of worse than necessary unemployment, some of it very long term unemployment, unless we act.

In the worst case, they’ll ask why we didn’t do more.

– ref. Cutting unemployment will require an extra $70 to $90 billion in stimulus. Here’s why – https://theconversation.com/cutting-unemployment-will-require-an-extra-70-to-90-billion-in-stimulus-heres-why-141376