Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Criena Fitzgerald, Honorary Research Fellow, Faculty of Arts, Business, Law and Education, University of Western Australia

We’ve been reminded about avoiding hugging or kissing, especially among large family groups, in light of the recent Melbourne coronavirus clusters.

But alerting the public to the potential for kissing to spread infectious diseases isn’t new. It’s been a feature of past pandemics, including the scourge of tuberculosis (or TB) in Australia a century ago.

In the first half of the 20th century, people with TB were advised to stop kissing to protect their friends and family from contracting the dreaded disease.

In 1905, delegates at an International Congress on Tuberculosis in Paris described kissing as “dangerous, detrimental and responsible for countless diseases”.

A minority of overly enthusiastic public health physicians suggested banning kissing altogether.

In Western Australia in 1948 an article in the Tuberculosis Association pamphlet warned “Kissing can be Dangerous: Doctors and Married Men are agreed on this”.

Showing bodily restraint was one of the few weapons against TB before the antibiotic streptomycin and other drugs became widely available after the end of the second world war and into the 1950s.

Other measures, with which we are familiar today, included sanitation and social distancing.

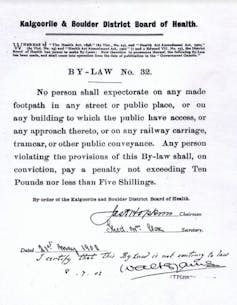

Laws and by-laws prohibiting spitting in public were introduced. Publicans had to provide spittoons for customers to prevent the spread of the disease. And people with TB had to spit into a jar, which they carried with them, or a tissue (known as Japanese paper), which they burnt after each use.

“Consumptives” (people with TB) were advised to cover their mouth when coughing or sneezing and not to speak near other people’s faces.

They were cautioned against drinking alcohol because even mild inebriation could make them careless in their behaviour and a danger to friends and family.

The message was clear. TB was a disease of the individual and any reckless or insanitary behaviour could infect others.

Extra cleanliness at home was encouraged. Regular dusting with a damp cloth kept surfaces clean and safe. Housewives were instructed to dampen the floor with wet tea leaves to prevent infected dust from contaminating the air and endangering family members.

An infected person used separate plates, cups and utensils that were boiled to sterilise them.

They separated themselves from their family, sleeping outside in an airy shelter or on the verandah or sleep-out.

If a person died from the disease, public health officials burnt their clothing and bedding. Their books were possible sources of contamination and had to be aired in sunlight to kill any remaining germs.

Contact tracing and mass testing

Public health officials conducted contact tracing to identify people carrying or having been exposed to TB.

People gave a sputum (spit) sample, which was then sent for analysis. They were warned to isolate themselves until the results were known.

Having a chest x-ray became compulsory for all Western Australians aged 14 years and over from 1950. The population was x-rayed at special clinics set up in every city or by mobile x-ray vans that went to every country town. Other states had different policies. By the early 1960s, x-rays were compulsory around Australia.

Only those who had had their x-ray and complied with public health requirements were deemed “safe”. If they didn’t comply they were called a public health menace and a danger to society.

Anyone refusing to be x-rayed could be sent to jail, where they were x-rayed.

Isolation housed the sick, often for years

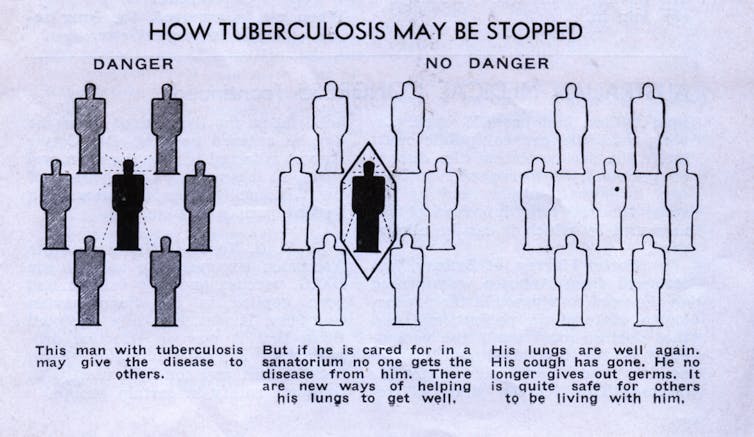

If people weren’t at home convalescing, they were sent to specially built isolation hospitals, known as sanatoria, to be treated with rest and fresh air. Sanatoria were regarded as a last resort because until 1947, and the advent of antibiotics, there was no cure for the disease.

In Western Australia from 1904 people went to the Coolgardie Sanatorium and from 1914 to Wooroloo Sanatorium, where they slept in the open air to disperse infection.

Incarceration in the sanatorium might last years or even a lifetime. Patients were unable to have close contact with visitors or see their children, except from a distance. Their incarceration was intended to protect the public from infection.

In the 1950s, special chest hospitals were built in cities offering a more modern approach to the disease, although sanatoria remained open. Patients could still spend more than a year in hospital even after a cure became available.

By 1958, as the TB pandemic waned and was eradicated, chest hospitals began to treat patients with other diseases.

What can we learn?

COVID-19 and tuberculosis are both branded as public enemies, wreaking havoc on the fabric of society and destroying lives. But unlike COVID-19, TB is caused by a bacterium, can be treated with antibiotics, and we have a vaccine against it.

Still, the World Health Organisation reported 1.5 million people worldwide died from TB in 2018.

Until we have a vaccine or treatment for COVID-19, social distancing, good hand hygiene, contact tracing, testing and self-isolation are among our chief weapons during this latest pandemic. And yes, kissing can still be dangerous.

– ref. ‘Kissing can be dangerous’: how old advice for TB seems strangely familiar today – https://theconversation.com/kissing-can-be-dangerous-how-old-advice-for-tb-seems-strangely-familiar-today-140172