Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Alexandra Baxter, PhD Candidate in Law/Criminology, researching human trafficking and modern slavery in Australia, Flinders University

Yes, there was slavery in Australia. Yes, there is slavery in Australia now.

It occurs as forced labour, sexual exploitation and forced marriage.

These situations rarely involve the actual chains and bars we commonly associate with historical slavery. They are nonetheless conditions of enslavement: a person is forced to work under threat; is controlled by another; is dehumanised or treated as a commodity; and is not free to leave.

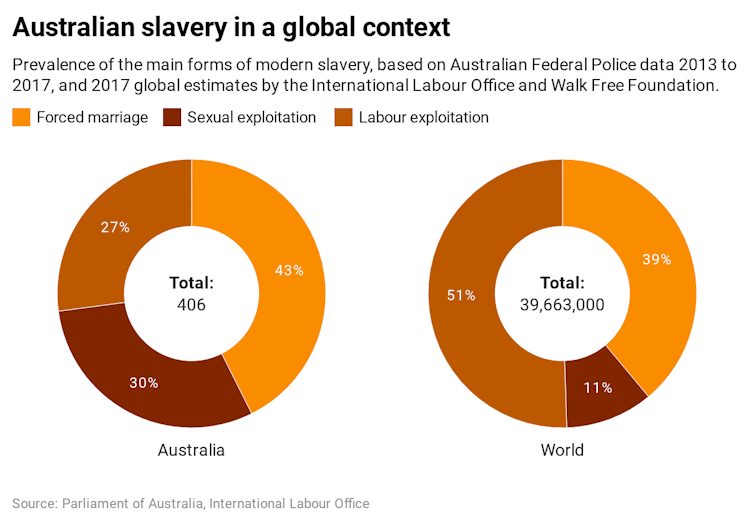

Relatively speaking, modern slavery is rare in Australia. Perhaps a few thousand people fit the strict definition, compared with about 40 million globally.

But every number is the story of a human being. Their stories are, however, rarely heard as modern slavery in Australia remains largely invisible.Australian statistics

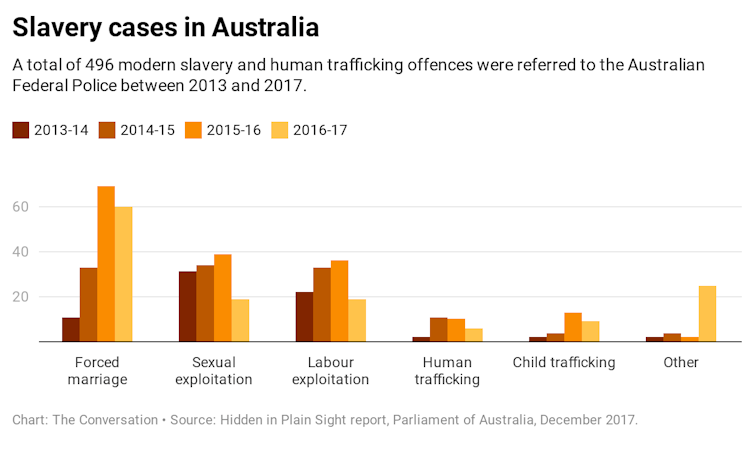

The best official data on modern slavery in Australia come from the Australian Federal Police, the agency to which all alleged human trafficking and slavery offences must be referred. Between 2013 and 2017, as reported to the federal parliament’s Inquiry into establishing a Modern Slavery Act, there were 496 referrals.

Read more: At last, Australia has a Modern Slavery Act. Here’s what you’ll need to know

The cases represent just a fifth of the iceberg, according to Anti-Slavery Australia, a research and policy centre that provides free legal services to victims of modern slavery. It estimates more than 80% of victims go undetected. This means about 2,000 more people in modern slavery than the AFP numbers indicate.

Forced labour

The most common form of slavery globally is (non-sexual) forced labour. An estimated 25 million people are forced to work through the use or threat of violence, or physical, emotional or financial restraints. Particularly prevalent is bonded labour or debt bondage – having to work to pay off a debt.

These practices thrive in the regulatory gaps of global supply chains. They are common, for example, in Indian textile making, in Thai fishing and in Chinese manufacturing.

In Australia such cases are relatively uncommon.

The first conviction under forced labour laws enacted by the federal parliament in 2013 was in April 2019. The case involved a Brisbane couple, Isikeli and Malavine Pulini, who were sentenced to five and six years’ jail respectively for forcing a Fijian woman to work as their domestic servant for eight years.

The woman had previously worked for the Pulinis in Tonga from 2001 to 2006. In 2008 they enticed her to Brisbane on a tourist visa, then took her passport from her. They manipulated her desire to stay in Australia and made her work long hours as nanny, cook, maid and cleaner. They paid her $150 to $250 a fortnight. She fled in 2016.

As the crown prosecutor Ben Power observed, this was “a secret hiding in plain sight” for eight years.

The majority of victims remain hidden for a long time. Commonly contributing to their invisibility are language barriers, a fear of immigration authorities, and an ignorance of Australian laws. Thus, while we can make estimates of the numbers of people caught in these situations, there might be more cases than we think.

Sexual exploitation

More common in Australia than labour exploitation, according to the AFP numbers, is sexual exploitation, which represents about 30% of slavery cases.

Sexual exploitation involves a person having to perform sex work due to coercion, threats or deception. To the extent this is done for the exploiter’s commercial gain, the International Labour Office considers sexual exploitation a form of forced labour.

One such case to end in a successful sexual slavery conviction is the November 2019 sentencing of Rungnapha Kanbut to eight years in jail for keeping two Thai women as slaves.

The two women came to Australia to do sex work. The man who made their travel arrangements took naked photos of them. The threat of these being posted on the internet was later used to deter the women from fleeing.

When they arrived in Australia, Kanbut took their passports and told them they needed to pay off a $45,000 debt. They worked up to 12 hours a day at multiple Sydney brothels. Most of their earnings went to Kanbut.

They were, as the judge put it, effectively kept “in a prison without bars”.

Read more: Human trafficking and slavery still happen in Australia. This comic explains how

Forced marriage

Forced marriage appears the most prevalent form of modern slavery in Australia. It involves being tricked, forced or coerced into a marriage without full consent. Of the estimated 15.4 million people in such arrangements globally, 13 million are female.

Research suggests victims of forced marriage in Australia are mostly the children of first-generation migrants from places such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Somalia and Fiji (though it should be noted the practice is in no way limited to specific nations or cultures).

An example is the case of an Australian-born teenager whose strict Indian-born parents tricked her into travelling to India on the premise of marrying the man she loved but then extorted her into marrying someone else.

The teenager had angered her parents by conducting a long-distance relationship then moving from Sydney to Melbourne to live with her chosen boyfriend.

They finally cajoled her into agreeing to a wedding in India as part of a reconciliation. But once the wedding party was in India, they took her passport and threatened to have her boyfriend’s mother and sister kidnapped and raped if she didn’t do what they said. So she did.

This case has a comparatively happy ending. The Family Court of Australia declared the marriage void.

But for many women there are many barriers to getting to court. These are complex situations compounded by social stigma, family pressure, fear of violence and cultural and gender expectations.

Read more: Dowry abuse does exist, but let’s focus on the wider issues of economic abuse and coercive control

Complex problems, complex responses

Each form of modern slavery is complex. Each requires a different policy response.

Forced marriage needs more of a “soft approach”, including consultation and education strategies, and prevention and empowerment opportunities that engage whole communities.

Sexual exploitation requires addressing the reasons that lead women into sex work and then to become part of the cycle of exploitation.

With forced labour, Australia’s Modern Slavery Act provides a focal point to promote accountability in business supply chains.

That wouldn’t have helped the victim of the Pulinis, though. In her case, as is uncounted others, the ability to hide in plain sight is slavery’s first defence.

So, along with policy measures, there’s also a need to heighten community awareness. We all have to be able to better spot the signs of slavery even without chains and bars.

– ref. Forced labour, sexual exploitation and forced marriage: modern slavery in Australia hides in plain sight – https://theconversation.com/forced-labour-sexual-exploitation-and-forced-marriage-modern-slavery-in-australia-hides-in-plain-sight-140838