Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Claire Breen, Professor of Law, University of Waikato

New Zealand is often described as a great place to grow up. We must also ask ourselves whether it is a great place to grow old.

The question becomes increasingly urgent as the impact of COVID-19 becomes clearer. While New Zealand has been one of a small number of countries to have seemingly controlled the spread of the virus, it has been older people who have borne the brunt of the disease.

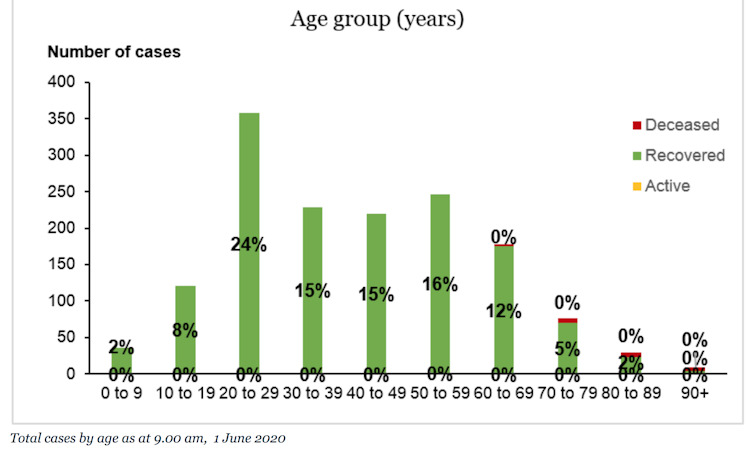

The elderly have not only died and become critically ill in greater numbers, as shown below, they have also suffered most under the stringent control measures adopted and from lapses in adequate health care.

There has been no shortage of debate about the impact of New Zealand’s strict lockdown on rights and liberties. But, given the burden of the disease has fallen mostly on older New Zealanders, their absence from that debate speaks volumes.

The establishment of an official advocate for the elderly is clearly overdue.About 15% of the population is aged 65 or older and that will double in the next few decades. The 22 New Zealanders who died from COVID-19 were 60 and older. Many of those deaths occurred in residential care facilities that struggled to adequately test residents and staff or provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and training.

Read more: Low staff levels must be part of any reviews into the coronavirus outbreaks in NZ rest homes

New Zealand’s aged care has fallen behind

This situation is sadly ironic because New Zealand has been a world leader in passing laws to protect older people, starting with the Old Age Pensions Act in 1898. Nearly a century later, the Human Rights Act 1993 prohibited discrimination on the basis of age.

In fact, the United Nations was still unsure whether this type of discrimination applied to older people’s rights to health, housing, work and social security. It wasn’t until 2009 that it finally concluded it did.

More generally, the rights of older people are not enshrined in any dedicated global human rights treaty. There are longstanding plans of action and principles in this area, but these fall into the category of “soft law”. They do not create legally binding obligations for countries.

Nonetheless, the UN is now focusing more on the human rights of older people and is considering whether there should be a treaty. It has taken a further step by appointing a UN Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older people.

Rosa Kornfeld-Matte, who held the role until recently, visited New Zealand at the invitation of the government just before we locked down due to COVID-19. Her findings suggest New Zealand’s leadership in protecting the rights and interests of older people has stalled.

UN expert’s call for a commissioner

Although there were things to be proud of in what Kornfeld-Matte found, including recent government strategies to cope with an ageing population, and our universal superannuation, there were also concerns.

Those included violence, poverty, affordable housing, availability of long-term care workers, structural biases in the health system that disproportionately affect Māori and Pasifika, and increasing rhetoric portraying the elderly as a burden.

To deal with these issues Kornfeld-Matte called for the establishment of “an independent national commissioner on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons”.

There is real merit in this recommendation. Although there is a minister and an Office for Seniors that has developed commendable strategies, there is still a risk this approach to advocacy will either be too timid or too tied to the views of whichever political party is in power.

NZ already has good models to copy

New Zealand already has a number of commissioners who are obliged to represent the interests of particular groups or concepts. Their advocacy role is based in legislation and they are independent of any political party or the partisan reach of any political cycle.

The best example is the Commissioner for Children whose role it is to advocate for the youngest New Zealanders. In the nearly two decades since its establishment, the Office of the Commissioner has managed to develop a system of advocacy across a wide range of areas, including children in the judicial system, children’s welfare, with the placement of children into state care.

The commissioner has consistently highlighted the issue of child poverty and hailed the passing (with cross-party support) of the Child Poverty Reduction Act in 2018 as “a historic cause for celebration”. The commissioner has the support of an international legal framework that has been accepted by every UN member state except the US.

Fortunately, New Zealand has been spared the devastation COVID-19 has caused elsewhere. But our lives have still been changed dramatically. The challenge now is to ensure the voices of those most at risk from the disease (and from the current means of controlling it) are heard loudly and clearly.

The appointment of an independent national commissioner to advocate for older New Zealanders would be a significant step towards restoring this country’s reputation as a great place to live – at any age.

– ref. The coronavirus crisis shows why New Zealand urgently needs a commissioner for older people – https://theconversation.com/the-coronavirus-crisis-shows-why-new-zealand-urgently-needs-a-commissioner-for-older-people-139383