Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Daniel Johnston, Research Affiliate, University of Sydney

Being close to others is intrinsically associated with theatre.

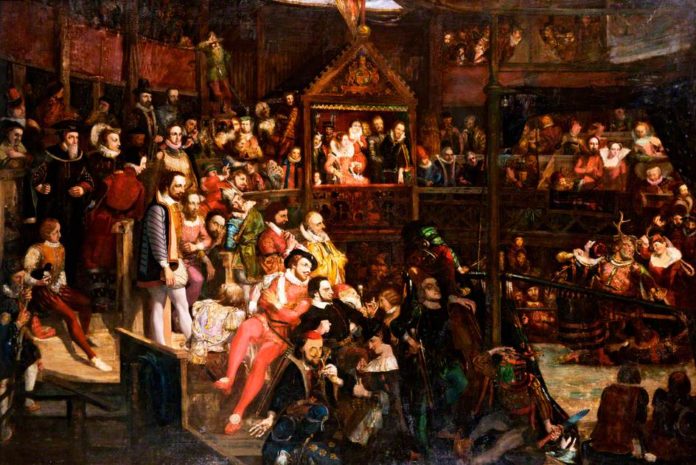

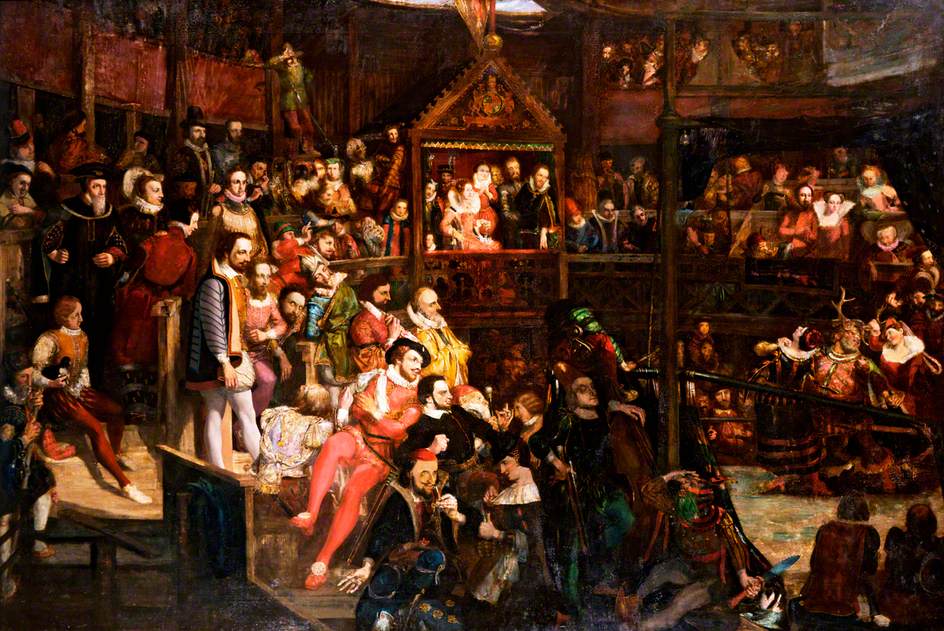

In Shakespeare’s London, theatre gatherings were condemned by the Puritans as evil. They thought the plague spread by theatre crowds was God’s punishment on the wicked for indulging in pastimes such as acting.

The shutting down of Broadway and the West End gives an eerie historical parallel to a world we thought was well in the past. Meanwhile, COVID-19 poses as an existential threat for Australia’s fragile performing arts sector.

While some artists look to stream performances online, there is something missing without others “being there” to witness performance in the flesh. Proximity and touch are crucial to “liveness”.

Festivals of togetherness

Touch is commonly associated with ritual through what anthropologist Victor Turner calls “communitas” – a shared and equal feeling of togetherness. In the Catholic mass, members of the congregation shake hands during the “sign of peace” creating a feeling of community. The Maori pōwhiri (welcoming ceremony) culminates in the “hongi” (pressing noses together). The Hajj is characterised by close embodied proximity of believers at the holy site in Islam.Touch can be important to cultural festivals too. Performance anthropologist J. Lowell Lewis notes that in Brazil’s Carnival:

the degree of close contact is quite important to the sense of a successful festival, for many, and is directly related to a positive valuation of what they call movimento (literally, movement; figuratively, something like the English colloquial sense of “where the action is” at a party scene or perhaps a “happening” situation) …

Live arts and theatre might not be founded in grand narratives of religious and cultural belief, but they do bring people together in a common experience.

Touching histories in theatre

From the ancient Greeks through to the Romans and Middle Ages, there was a theory we are always in contact through an invisible “ether” that exists between bodies.

The famous Russian director and father of actor-training, Constantin Stanislavski, wrote about a “communion” between actors and audience through invisible rays of communication linking by what he called “irradiation”. He also talked about “grasp” on an audience in moments of inspiration.

Avant garde French poet and theatre-maker, Antonin Artaud, speculated about “theatre and the plague” and dreamt of a direct communication of thought and meaning through the body in live performance.

Brazilian theatre-maker and political activist, Augusto Boal, developed theatre games in which touch was crucial for bringing a community together through what he called Theatre of the Oppressed. Proximity and feeling were important for participants understanding each other’s perspective and exploring different ways we might engage in social and political change.

More recently, we have seen the rise of immersive theatre which breaks the fourth wall and allows audiences and performers to interact in specific surroundings, often through improvisation.

Tactility is part of what ethnographer Clifford Geertz calls our “matrix of sensibility”. Skin-to-skin contact is crucial to the mother-infant relationship and our very first awareness of the world.

But with new media, seeing is the dominant way we tend to consume entertainment. The risk is that we might lose a sense of feeling and responsibility.

Philosophy and Ethics

In many ways, touch is fundamental to the way we come to know the world as theorised by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. The phrase, “getting a handle on something” can mean practical and emotional knowledge about the world. So when we say a performance was “touching”, it can also be an embodied feeling of change.

Arts and theatre companies are already finding innovative ways of reaching audiences. Part of the thrill of being at a live event is a sense of danger. Audience members see each other. Things might go wrong. You might be handpicked as a volunteer from the audience. And there is a mutual obligation developed through laughter, silence and applause.

How these dangers will transmit via Zoom, Skype or Instagram Live remains to be seen.

Read more: When one door closes, open a window – 14 sites with great free art

Evolution

Perhaps limiting touch will serve to increase the meaning of proximity on the occasions that it does occur.

Our heightened awareness of touch and proximity might have benefits in terms of staying away from others if we are unwell, washing hands and maintaining personal hygiene. Lady Macbeth’s untimely demise might serve a double purpose if we say her famous “Out damned spot!”speech twice while scrubbing and rinsing.

In the meantime, new norms around touch and proximity will emerge and performance will play an important part in reflecting and changing social attitudes.

– ref. The power of proximity and the theatre of touch: what losing live audiences may mean for theatre – https://theconversation.com/the-power-of-proximity-and-the-theatre-of-touch-what-losing-live-audiences-may-mean-for-theatre-133515