Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Averyl Gaylor, PhD Candidate in History and Manager, Centre for Health, Law and Society at La Trobe Law School, La Trobe University

Today’s latest medical advice is to wash our hands to the chorus of songs from the likes of Lizzo, Gloria Gaynor or Beyoncé. This is to mitigate the boredom of washing to Happy Birthday … twice!

Public health strategies have been linked to popular culture before. In the 1930s, it was modern dance that taught Melburnians how to perform personal hygiene.

Dance classes were so popular the Sun News Pictorial reported:

One dance instructor, Russian immigrant Sonia Revid, specialised in the instruction of hygiene through movement.Doctors, Barristers, other professional men are learning or relearning dance, and there are busy classes for business and married girls, tiny toddlers, and even mothers of families, and social heavyweights.

Revid choreographed and performed ballets that taught audiences how to brush their teeth. She also published a pamphlet outlining the importance of personal hygiene. The City of Melbourne’s medical officer, John Dale, publicly praised Revid’s efforts and parents were advised to enrol their children in her classes.

Body and soul

Revid had opened her dance studio in Collins Street, Melbourne, in 1933, a year after her arrival in Australia.

The Sonia Revid School for Art Dance and Body Culture was promoted as ensuring “physical well-being and lasting health” and provided “lessons to correct specific physical defects, such as obesity, flat feet, unshapely hands, self-consciousness and shyness”.

By 1936, Revid was promoting her method as not only a way to stay fit and healthy but also as means of acquiring a “consciousness of cleanliness”.

Revid asserted the capabilities of her practice based on the evidence of a medico-social experiment she conducted on a group of poor children in 1935. Revid wanted to see whether poor children who lived in the then “slums” of Fitzroy could learn to distinguish between hygienic and unhygienic practices through dance education.

Poor hygiene had been associated with a lack of social responsibility and immorality and so Revid’s published pamphlet asked through metaphor: Do Slum Children Distinguish Light From Dark?

From her observations, Revid concluded modern dance had a cleansing capacity – performing a sort of physical and spiritual bath. Not only did it teach children how to identify hygienic and unhygienic practices, she wrote, but imparted a more hygienic constitution.

Don’t forget to smile

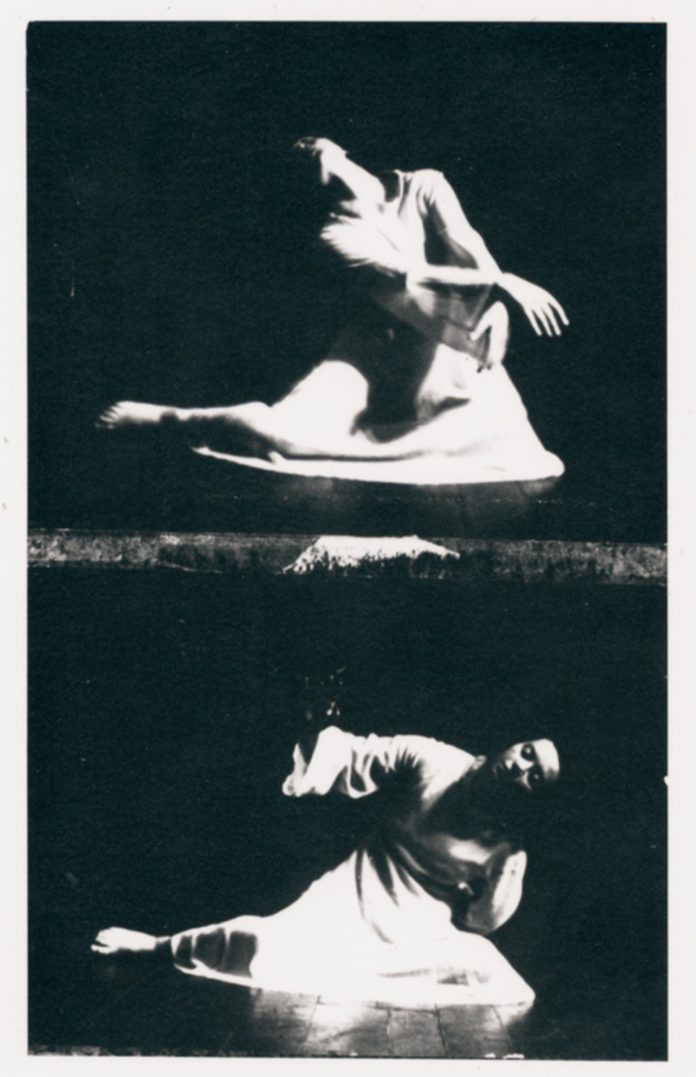

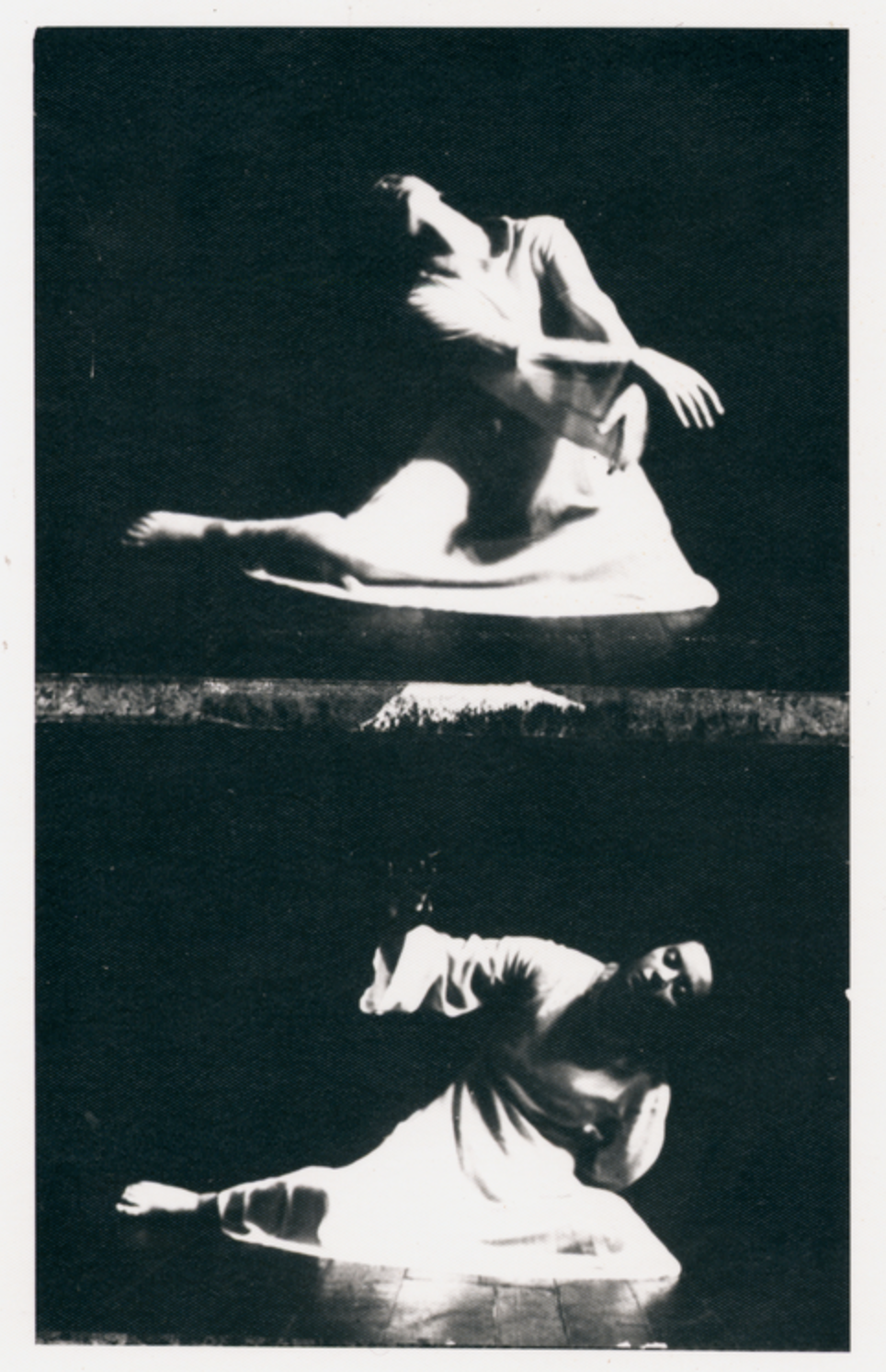

Emboldened by her belief in the hygienic potential of dance, Revid began to include ballets with public health messages in her performance repertoire.

Her 1938 ballet, Little Fool and Her Adventures, instructed audiences how to brush their teeth correctly and portrayed the painful consequences of poor dental hygiene.

The ballet was first performed at the University of Melbourne’s Union House Theatre and later at school halls such as at Melbourne Church of England Girls Grammar School, now Melbourne Girls Grammar. It was performed in four parts. Part one was an introduction to the protagonist, Little Fool, and to the themes of the ballet.

Little Fool Has a Toothache, the second section, told of the pain associated with dental decay. It was dramatically enhanced by a thumping musical score by the French composer, Charles Gounod, titled Funeral March of a Marionette. The score alluded to the serious medical consequences of poor dental hygiene. Audiences reported its repetitive rhythm reminded them of the thumping pain of a sensitive nerve.

The ballet’s climax was in part three: The Toothache Leaves a Mark on Little Fool – She imagines she is pursued by evil spirits. This section was ominously danced to Camille Saint-Saëns’s Danse Macabre (known in English as Dance of Death). The choreography showed Little Fool overcome by delirium.

Revid’s ballet concluded with a positive message of calm vigilance. Little Fool overcame her sore tooth and departed the stage to a lively and uplifting tune.

Lessons today

Little Fool remained in Revid’s repertoire for many years, providing hygienic instruction and a cautionary public health warning to all who saw it.

Revid’s dance classes and her performances taught the importance of daily hygiene and kept the community informed of best practices through the fluctuating realities of Melbourne’s public health.

With advances in medicine and technology, such as vaccines, we often take the basics for granted, losing sight of the importance of thorough handwashing until a global pandemic reminds us of its preventive power.

Although hygienic instruction hasn’t been a part of popular artistic culture for a while, in 2020 Beyoncé and Lizzo are taking matters into their own clean hands.

– ref. Hidden women of history: Sonia Revid created public health ballet at the height of ‘dance fever’ – https://theconversation.com/hidden-women-of-history-sonia-revid-created-public-health-ballet-at-the-height-of-dance-fever-132978