Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

The spread of the coronavirus has brought us all face to face with the remorseless logic of exponential growth. A handful of cases has turned into dozens, then hundreds, then thousands.

If current attempts at containment fail, we can expect many millions of cases around the world.

Read more: One word repeated 9 times explains why the Reserve Bank cut: it’s ‘coronavirus’

The government’s economic policy response reflects this dawning reality. The exponential growth of the virus has been matched by growth in the magnitude and scope of the required response.

While the virus was developing in China, and even in the midst of the bushfire crisis, the government was insisting that its wafer-thin surplus would be delivered as promised.Denial for a while…

Even after it became evident that the budget would be in deficit and the economy close to recession (at least in terms of the widely-used “two quarters of negative growth” criterion), the government’s primary concern was to avoid validating the Rudd government’s response to the global financial crisis.

Estimates of a package of A$2 to $5 billion were leaked, with a strong emphasis on a modest and targeted response, confined to specific sectors such as tourism. The universities, seen as tribal enemies by many in the government, got no sympathy.

Read more: Morrison’s coronavirus package is a good start, but he’ll probably have to spend more

Rather than being treated an export earner in trouble, universities were blamed for relying too much on the Chinese market. The idea of boosting Newstart and other welfare payments was dismissed out of hand.

As the package developed, the power of the “go hard, go early, go household” logic that drove the 2008 response of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and Treasury Secretary Ken Henry became evident.

…then a focus on what might work

The figure being bandied about rose to $10 billion, and the government’s attempts at product differentiation became ever feebler.

This stimulus, it was claimed, would rely on existing programs (an attempt to keep faith with the spurious attacks on Rudd programs like the school-hall focused Building the Education Revolution).

It would be wound down as soon as the crisis was over (something Rudd’s treasurer Wayne Swan spent years trying and failing to do).

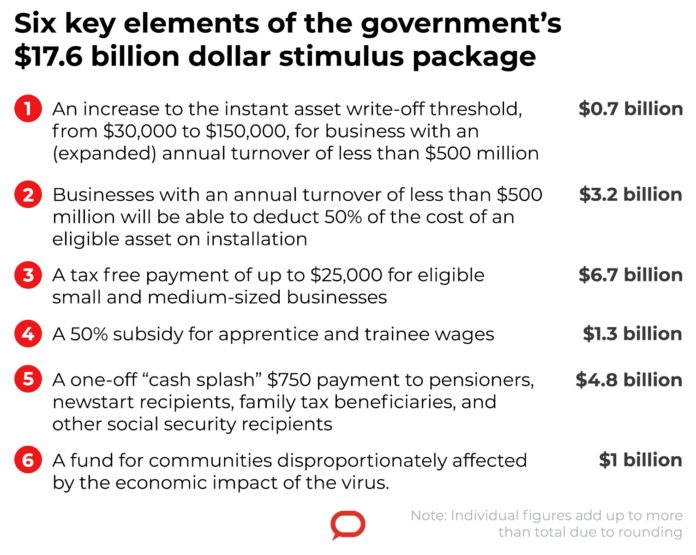

Now we have the announcement of a nearly $18 billion package which is virtually a repeat of Labor’s response to the global financial crisis.

The central elements are a cash handout aimed at sustaining consumer demand, and broad measures to stimulate investment.

Allowing for inflation and population growth, the almost $18 billion cost of this package is very similar to the $10 billion cost of the Rudd government’s first stimulus. It’s highly likely that, as in the GFC, more will be needed in future.

Those numbers doesn’t take account of the impact of the crisis on tax revenues and unemployment benefits.

It is highly likely that the economic aftershocks will be felt for years to come, and to me, it seems possible the impact on the budget may be well over $100 billion by the time Australia recovers.

There’ll be lessons when this is over

The remaining targeted measures to assist specific sectors like tourism have their parallel in the Rudd government’s rescue of the car finance industry through the Ozcar scheme, which gave rise to the (then) infamous “Utegate” scandal.

Looking ahead, the crisis response should kill off not only the idea that a surplus is the hallmark of responsible economic management, but also the absurdity of extending the standard four-year forward estimates period to ten-year projections, which formed the basis of tax cuts legislated years ahead of time.

Read more: When it comes to sick leave, we’re not much better prepared for coronavirus than the US

As the current crisis and the global financial crisis have shown, even an annual budget can be derailed by an unforeseen shock. Attempting to fix policies ten years in advance is a fools’ errand.

More broadly, this is yet another instance in which policies influenced by the market ideology that took hold in the 1970s has damaged us.

The economic impacts of coronavirus will be made worse by the casualisation of the workforce and the decades-long freeze on Newstart and other welfare payments.

A modern society can only function properly with a strong government and a commitment to looking after everybody. Perhaps the enforced isolation we are likely to face in the coming months will give us time to rethink.

– ref. The coronavirus stimulus program is Labor’s in disguise, as it should be – https://theconversation.com/the-coronavirus-stimulus-program-is-labors-in-disguise-as-it-should-be-133383