Source: The Conversation (Au and NZ) – By Rohan Fisher, Information Technology for Development Researcher, Charles Darwin University

The tropical savannas of northern Australia are among the most fire-prone regions in the world. On average, they account for 70% of the area affected by fire each year in Australia.

But effective fire management over the past 20 years has reduced the annual average area burned – an area larger than Tasmania. The extent of this achievement is staggering, almost incomprehensible in a southern Australia context after the summer’s devastating bushfires.

Read more: I made bushfire maps from satellite data, and found a glaring gap in Australia’s preparedness

The success in northern Australia is the result of sustained and arduous on-ground work by a range of landowners and managers. Of greatest significance is the fire management from Indigenous community-based ranger groups, which has led to one of the most significant greenhouse gas emissions reduction practices in Australia.

As Willie Rioli, a Tiwi Islander and Indigenous Carbon Industry Network board member recently said:Fire is a tool and it’s something people should see as part of the Australian landscape. By using fire at the right time of year, in the right places with the right people, we have a good chance to help country and climate.

Importantly, people need to listen to science – the success of our industry has been from a collaboration between our traditional knowledge and modern science and this cooperation has made our work the most innovative and successful in the world.

A tinder-dry season

The 2019 fire season was especially challenging in the north (as it was in the south), following years of low rainfall across the Kimberly and Top-End. Northern Australia endured tinder-dry conditions, severe fire weather in the late dry season, and a very late onset of wet-season relief.

Despite these severe conditions, extensive fuel management and fire suppression activities over several years meant northern Australia didn’t see the scale of destruction experienced in the south.

This is a huge success for biodiversity conservation under worsening, longer-term fire conditions induced by climate change. Indigenous land managers are even extending their knowledge of savanna burning to southern Africa.

Burn early in the dry season

The broad principles of northern Australia fire management are to burn early in the dry season when fires can be readily managed; and suppress, where possible, the ignition of uncontrolled fires – often from non-human sources such as lightning – in the late dry season.

Traditional Indigenous fire management involves deploying “cool” (low intensity) and patchy burning early in the dry season to reduce grass fuel. This creates firebreaks in the landscape that help stop larger and far more severe fires late in the dry season.

Essentially, burning early in the dry season accords with tradition, while suppressing fires that ignite late in the dry season is a post-colonial practice.

Savannah burning is different to burn-offs in South East Australia, partly because grass fuel reduction burns are more effective – it’s rare to have high-intensity fires spreading from tree to tree. What’s more, these areas are sparsely populated, with less infrastructure, so there are fewer risks.

Read more: The burn legacy: why the science on hazard reduction is contested

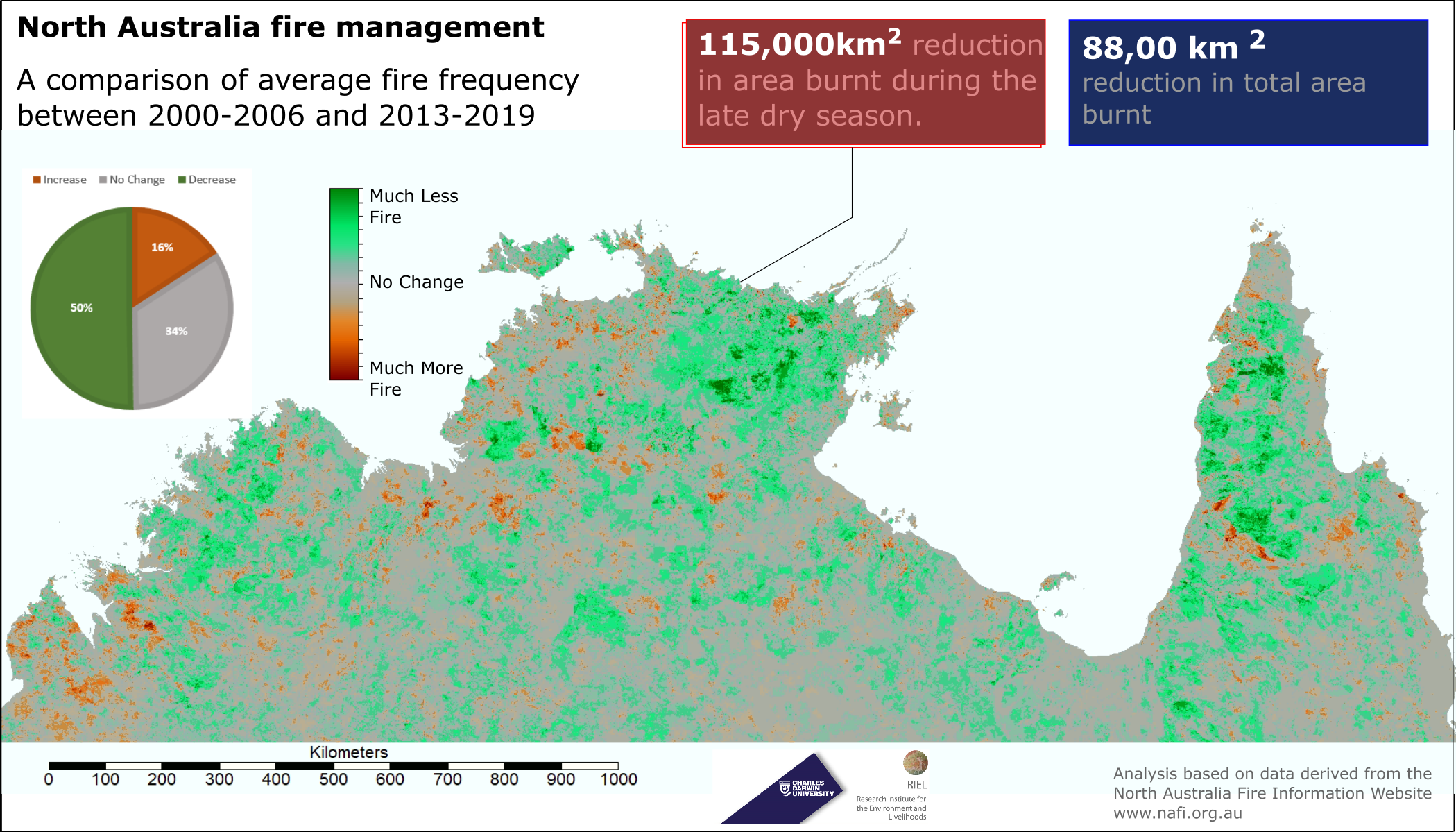

Satellite monitoring over the last 15 years shows the scale of change. We can compare the average area burnt across the tropical savannas over seven years from 2000 (2000–2006) with the last seven years (2013–2019). Since 2013, active fire management has been much more extensive.

The comparison reveals a reduction of late dry season wildfires over an area of 115,000 square kilometres and of all fires by 88,000 square kilometres.

Combining traditional knowledge with western science

The primary goals of Indigenous savanna burning projects remain to support cultural reproduction, on-country living and “healthy country” outcomes.

Savanna burning is highly symbiotic with biodiversity conservation and landscape management, which is the core business of rangers.

Ensuring these gains are sustainable requires a significant amount of difficult on-ground work in remote and challenging circumstances. It involves not only Indigenous rangers, but also pastoralists, park rangers and private conservation groups. These emerging networks have helped build new savanna burning knowledge and innovative technologies.

Read more: Our land is burning, and western science does not have all the answers

While customary knowledge underpins much of this work, the vast spatial extent of today’s savanna burning requires helicopters, remote sensing and satellite mapping. In other words, traditional burning is reconfigured to combine with western scientific knowledge and new tools.

For Indigenous rangers, burning from helicopters using incendiaries is augmented by ground-based operations, including on-foot burns that support more nuanced cultural engagement with country.

On-ground burns are particularly important for protecting sacred sites, built infrastructure and areas of high conservation value such as groves of monsoonal forest.

Who pays for it?

A more active savanna burning regime over the last seven years has led to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of more than seven million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Read more: Savanna burning: carbon pays for conservation in northern Australia

This is around 10% of the total emission reductions accredited by the Australian government through carbon credits units under Carbon Farming Initiative Act. Under the act, one Australian carbon credit unit is earned for each tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent that a project stores or avoids.

By selling these carbon credits units either to the government or on a private commercial market, land managers have created a A$20 million a year savanna burning industry.

What can the rest of Australia learn?

Savanna fire management is not directly translatable to southern Australia, where the climate is more temperate, the vegetation is different and the landscape is more densely populated. Still, there are lessons to be learnt.

A big reason for the success of fire management in the north savannas is because of the collaboration with scientists and Indigenous land managers, built on respect for the sophistication of traditional knowledge.

This is augmented by broad networks of fire managers across the complex cross-cultural landscape of northern Australia. Climate change will increasingly impact fire management across Australia, but at least in the north there is a growing capacity to face the challenge.

– ref. The world’s best fire management system is in northern Australia, and it’s led by Indigenous land managers – https://theconversation.com/the-worlds-best-fire-management-system-is-in-northern-australia-and-its-led-by-indigenous-land-managers-133071