Source: Medium [https://bit.ly/2o1ytEo]. Analysis by Ronald F Pol from AMLassurance.com (Dr Pol’s PhD is in policy effectiveness, outcomes and money laundering)

The modern anti-money laundering system (which makes banks and other firms check identity documents and scan billions of financial transactions) doesn’t stop crime. Criminals keep up to 99.9% of the earnings from misery, and a scheme meant to ‘protect the financial system’ causes severe social and economic harm.

So, where did it all start to go wrong?

Good intentions and ‘voluntary coercion’

Today’s anti-money laundering movement began at a G7 summit in 1989. The seven big industrialized nations circumvented the usual treaty-based consensus to establish an ad-hoc body to use financial flows to help prevent drug trafficking. The Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF) later targeted money laundering associated with other profit-motivated crime and terrorist financing. All worthy aims.

For many years, however, few nations signed up to the ‘compliance with rules based on standards’ model that FATF advocated. Rather than trying to develop an alternative model, perhaps better aligned with countries’ anti-crime efforts, FATF rated compliance with 40 ‘recommendations’ (then claimed to reflect the effectiveness of anti-money laundering regimes) and began a ‘name and shame’ campaign — publicly denouncing nations not ticking enough boxes.

FATF no longer needed to persuade countries that its prescription worked. Nor demonstrate how it helps reduce crime and the social and economic harms caused by serious profit-motivated crime like drug, human, wildlife and arms trafficking, fraud, corruption, and tax evasion. Assumptions that it ‘should’ do so, or assertions that it ‘would,’ was enough, apparently.

In any event, countries can’t afford to ignore FATF because banks use its ratings as a proxy for risk in their dealings with other countries. Sovereign nations are effectively forced to submit to evaluation and implement the laws that FATF demands, to maintain vital access to international financial markets.

Unsurprisingly, momentum to join the anti-money laundering ‘family’ rapidly escalated. Facing the risk of exclusion from financial markets, seemingly more countries than there are countries ‘voluntarily’ joined the anti-money laundering movement. With 205 participants, the anti-money laundering movement counts more jurisdictions than even the United Nation’s 193 nation-states. (Mainly because FATF includes semi-autonomous jurisdictions separately, like China and Hong Kong, the UK’s dependencies and overseas territories, and islands formerly known as the Dutch Antilles).

Despite the now global ubiquity of money laundering controls, FATF admits that it still “pressures” nations to meet its demands, if they want to “maintain their position in the global economy.”

But, whether it works, or not (I’ll return to that shortly), unilateral financial sanctions and the anti-money laundering system — both part of a policy arsenal available to few nations — cause significant harm, and disproportionately affect smaller and less powerful countries.

Measures meant to ‘protect’ the financial system also harm economies

Pakistan’s Prime Minister, a former international cricketer and cancer campaigner, Imran Khan, recently decried the “devastating” impact of illicit financial flows causing “poverty, death, and destruction in…the developing world.”

He rued billions of dollars leaving developing countries, siphoned into offshore accounts, tax havens and real estate in Western capitals, and denounced a lack of political will in those countries to help recover looted funds, “because they gain from it.”

As well as the economic damage Khan described — some might say due to Pakistan’s failure to meet FATF standards (and a recent empirical study suggests a correlation between terrorism financing and the incidence, scale and location of terrorist attacks) — the anti-money laundering system also inflicts harm.

Compounding Pakistan’s difficulties, an evaluation report (embargoed since August) was released a few days after Khan’s UN speech in September, excoriating the ‘effectiveness’ of Pakistan’s anti-money laundering regime. Reportedly after lobbying from powerful nations, FATF had earlier added Pakistan to its ‘grey list’ of countries with claimed ‘strategic deficiencies’ (in June 2018), so Khan presumably needed no reminder that the anti-money laundering system inflicts social and economic damage. (Wielding the stick of financial exclusion, there may be little perceived need for subtlety. In October, FATF gave Khan a reminder anyway, bluntly warning that it might blacklist Pakistan at its next plenary in February 2020).

In any event, a similar theme — of deliberate, devastating economic damage inflicted by powerful nations for political reasons — was expressed by many other leaders at the annual UN General Assembly in New York at the end of September.

Many Caribbean nations, for instance, voiced dismay about the use of the financial system to hinder the economic development of small countries that try to compete with powerful nations.

Dr Ralph Gonsalves, Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, decried the “weaponizing of trade and the banking system” as a “thinly-veiled war [based on stereotypes and paternalism] against…developing States under the guise of…reducing illicit financial flows.”

Dr Timothy Harris, Prime Minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis, described “unfair” blacklisting and “de‑risking” (where global banks use blacklists and ratings as proxy risk assessments and cut ties with local banks) as an “existential threat” to small economies. Saint Lucia’s Prime Minister, Allen Chastanet, agreed, adding that small nations are grappling with restrictions imposed with no “credible evidence of wrongdoing” wreaking “irreversible damage.”

Mia Mottley QC and Dr Keith Rowley, the Prime Ministers of Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago spoke, respectively, about the “challenges” of blacklisting and “deep concern” over the loss of correspondent banks harming small nations, which, according to Prime Minister Gaston Browne of Antigua and Barbuda, continues the economic damage wrought by centuries of exploitation by slavery.

It is easy (and common) unreflectively to dismiss such protests as contrary to the expressed aim to protect the financial system. However, even trenchant supporters of the dominant anti-money laundering narrative might concede at least some merit in some complaints.

For example, professional advisers from the United States, United Kingdom, and other former colonial powers helped design financial systems now labeled ‘deficient,’ and their clients in those more prominent countries remain some of the most significant users of such services.

Moreover, countries like the US and UK offer many similar services to those for which smaller nations are disparaged (Delaware, anyone?) The United States also frankly admits that it’s a “major money laundering jurisdiction,” yet commands the default global currency and is big enough to avoid negative consequences of pejorative labeling. And more laundering likely takes place in a few big countries like the US and UK, untroubled by poor ratings and blacklists, than most other countries combined.

The reality, however, is that few other countries can avoid the impact of financial sanctions or poor anti-money laundering ratings.

Sudan’s newly installed Prime Minister, for instance, appointed in August after months of mass protests, sought the removal of sanctions punishing the Sudanese people for acts committed by the previous regime. Iraq’s President Salih called for action to combat corruption networks and regain stolen assets. Vanuatu’s Prime Minister, Charlot Salwai, denounced persistent colonial hegemony, and Cuba’s foreign minister condemned the “economic warfare” of “criminal” financial sanctions hindering his country’s progress.

Venezuela’s Vice-President, Delcy Rodríguez, a lawyer targeted with financial restrictions by multiple countries, described economic sanctions as the “preferred weapon of domination in the twenty-first century”, capable of wiping out the income of sovereign states “with the press of a single digital button”, and punishing innocent people and using their suffering “to bolster…hegemonic power.”

Disconcertingly from a Western viewpoint which considers democracies the strongest cheerleaders for democratic institutions on the global stage, it was Russia’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Sergey Lavrov, who championed equality in international relations. Concerned, apparently, with the fragmentation of the international community, Lavrov characterized the emergence of a ‘rules-based order’ as trying to replace established rules of international law with new ones based on self-serving schemes and political expediency favoring only some countries. He urged that global challenges should be addressed based on the inclusive nature of the UN Charter and the interests of all states.

It’s easy to dismiss grievances from ‘the usual suspects.’ Narratives about Russia’s ‘autocratic regime,’ Sudan’s ‘brutal dictatorship,’ Pakistan’s ‘support for terrorists,’ Cuba’s ‘refusal to move towards democratization,’ and Venezuela’s ‘illegitimate regime’ are well-rehearsed. Who has the time to check if reality is more nuanced than these familiar tropes from our own politicians and industry insiders? (Especially, if we’re honest, about countries we might perceive as ‘other’).

But, whether the ‘rules-based order’ is a force for good, as many Western nations contend, or risks undermining international law and equality between nations, as Russia claims, financial sanctions and the operation of the anti-money laundering system clearly cause harm. Deliberately.

Harms intended

Financial sanctions (mostly, US-imposed) and FATF blacklists, grey lists, and ratings all affect countries’ access to financial markets, with no apology for any damage caused. After all, severe restrictions are the point of such sanctions. As FATF explains, it “pressures” nations to meet its demands “in order to maintain their position in the global economy.”

It could be said that countries harmed by blacklists and poor anti-money laundering ratings are righteously punished for not adhering to norms of the rules-based order. After all, from a Western perspective, a rules-based order sounds comfortingly familiar and uncontroversial, like the rule of law.

But the ‘rules-based order’ increasingly prominent in recent years is ill-defined and plagued with differing assumptions. Simple questions reveal complex concerns. Who makes the ‘rules’? Can all countries participate equally in their development? Does the new ‘order’ disproportionately favor, or harm, some nations compared with others?

Disturbingly, in the anti-money laundering context the answers to such questions also convey overtones of rich vs. poor, big vs. small, ex-colonizer vs. former colonies, and ‘us’ vs. ‘them.’

A few years ago, for instance, Saint Lucia’s Prime Minister, Allen Chastanet, described the “painful example” of financial exclusion by powerful nations whose professional classes were “the very architects” of the economic development strategies for which Caribbean nations are being penalized. Moreover, the G20, which “designated itself” as the forum for collective international economic cooperation, excludes most countries. Ninety percent of nations are not members of that “unofficial and non-inclusive bloc,” so “were not involved in the solutions to the problems,” he added, “nor were we consulted on its appointment as the arbiters of our economic fate.”

Nonetheless, complaints by affected nations might still be dismissed as self-serving, if the anti-money laundering system works.

In other words, if enough discomfort forces countries to introduce or strengthen rules enabling a material impact on serious profit-motivated crime and terrorism, it might be worthwhile, at least in a collective sense. That, arguably, is the rationale of money laundering blacklists and ratings.

The only problem is the tyranny of truth: the anti-money laundering system doesn’t work.

Failure locked in

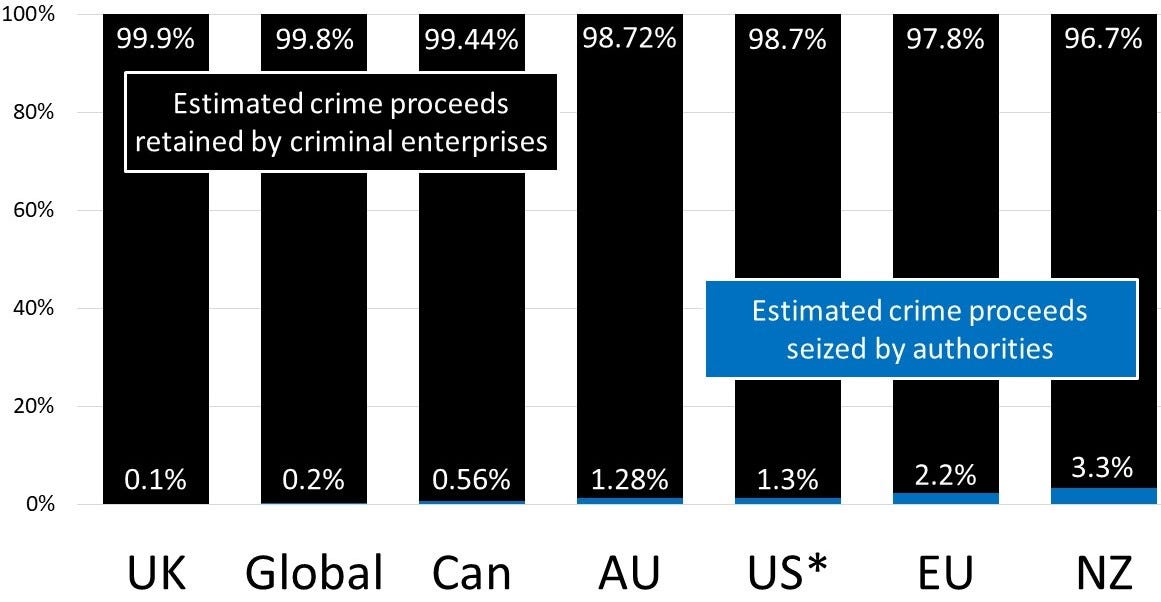

Despite trillions of dollars and 30 years of prodigious effort, the modern anti-money laundering experiment scarcely has the impact of a rounding error on criminal accounts. By UN measures, the ‘success rate’ of money laundering controls is inconsequential when authorities reclaim a puny 0.2 percent of illicit funds, allowing ‘Criminals Inc’ to keep up to 99.8 percent (my own research puts the figure at 99.9 percent, but who’s quibbling?)

Nonetheless, the practical reality is that reasoned criticism by suffering nations is unlikely to curb the use of economic sanctions. Instead, pressing other countries to the will of a more powerful force is a growth sport.

‘Naming and shaming’ alive and well

The European Union’s attempt to join the ‘name and shame’ World Series was denounced by the dominant player and criticized by countries labeled ‘bad.’ A new list of ‘external’ jurisdictions unilaterally declared ‘deficient’ —initially due to be re-issued this month — is still “on the agenda,” and is now expected in 2020. (Extending the ‘us vs. them’ theme, the EU only pejoratively labels ‘external’ countries, not its member states).

Although the EU methodology was heavily criticized, the system that it seeks to attach itself to remains astonishingly ineffective, for reasons persistently unaddressed. (Ironically, the European police agency, Europol, frankly recognized the scale of policy failure, but its finding that serious crime pays, seriously well, appears to have fallen mostly on deaf ears, like the United Nation’s earlier assessment).

Design flaws

There are many reasons for anti-money laundering’s failure. Most trace back to the rushed development of a compliance model unchanged in three decades, seldom questioned, and seemingly unquestionable. Perverse incentives also harm people trying to do what the system was originally intended to achieve. But the main problem is a persistent focus on the effort and activities to prove compliance rather than what’s needed to achieve better (crime prevention) outcomes.

For example, new ratings meant to fix the problem use the language of ‘effectiveness’ and ‘outcomes,’ absent a functioning effectiveness framework [research paper, free access to January 2020], thereby continuing the 30-year focus on effort rather than results. Despite FATF’s grandiose labeling of its flagship ratings ‘mutual evaluations’, a trio of professors found that there has been “minimal effort” at anti-money laundering evaluation, “at least in the sense in which evaluation is generally understood [in public policy and social science], namely how well an intervention does in achieving its goals.”

Moreover, the rating system’s tick-box mentality encourages a tick-box response to mitigate harms imposed by a system characterized more by good intentions and rhetoric than any cogent measure of effectiveness.

It is, therefore, unsurprising if ‘compliance’ is the unspoken objective of many governments (to ‘get the FATF tick’ and minimize adverse consequences from the system itself), rather than any meaningful crime prevention outcomes.

The hectic nature of anti-money laundering compliance also conceals the reality of poor outcomes. Complicated rules are designed like a giant stack of colanders to catch water, with each ‘gap’ ‘fixed’ by constantly extending money laundering controls to more transactions, businesses, and industries, and more ‘solutions’ touted (increased public/private sector collaboration, law enforcement integration, artificial intelligence, etc). With a steady stream of new ‘solutions’ constantly adding more colanders, it’s easy to miss the big picture, about how much ‘water’ the entire stack of colanders manages to catch. Most ‘solutions’ have some positive effect, but when all combined, over three decades, manage to trap less than one percent of criminal finances, the impact on crime seems marginal, at best.

Conclusion, and options for leaders

The anti-money laundering industrial complex affects every citizen — with higher fees and taxes to pay for hundreds of billions of dollars of compliance costs each year, plus the social and economic impact from serious crime, barely checked. It also makes banking difficult for millions of ordinary people and penalizes smaller, weaker nations, yet the modern anti-money laundering experiment is almost entirely ineffective.

Complicated laws, armies of regulators, and costly compliance tasks give the comfort of activity and feeling of security but don’t make us safe from serious crime and terrorism.

Authentic leaders keen to reduce the social and economic harms from serious profit-motivated crime and terrorism have a choice. They could blindly follow the orders of an unelected agency accountable to no country’s citizens, driven by a few powerful states, in order to get FATF’s tick of approval for implementing its standards, despite scarcely any impact on criminal finances.

Or, leaders might face up to the reality of anti-money laundering’s failure, and consider reframing the system to switch from less than one percent impact on crime into the 99 percent zone, as the G7 intended in 1989.

— — —

Postscript

If any leaders choose the second option, pragmatism suggests that they should still ‘get the FATF tick’ in the meantime.

(88 jurisdictions have so far been assessed in the current round of evaluations, and reports published. Many governments were surprised with lower than expected ratings, but a few — learning the unspoken lessons not recorded in any official guidelines — have begun to operate the system as it’s designed, if not intended, for better than expected ratings, irrespective any ‘real’ [empirical] risk, which, ironically, the current system doesn’t measure).

After all, retaining access to the financial system helps governments extend their own crime prevention capabilities, even if there’s no appetite to reframe the global anti-money laundering system for meaningful outcomes.